Fate has lovingly linked Mira, called Mimi, a prisoner of the Majdanek, Ravensbrück and Buchenwald camps, with Józef, the prisoner of Auschwitz. After the war, the woman and her lover ended up in Birkenau, where she helped to create a local museum. However, her intricate history began much earlier, in faraway France, where life had sent her family in pursuit of bread.

Mommy is impossible. He constantly insists that I should learn to sew, and I hate it with all my heart. Now she also insisted that if I don't master the stitches, patterns, and finally sew a soft, gray wool two-piece winter suit by myself, she won't let me go to Warsaw.

I love my mother and only because I do not want to disappoint her, I pore over our black uniform, trying to thread the thread for the first time. In its two drawers, my mother hides her greatest treasures:colorful buttons, rainbow-colored threads, rubber bands, sharp pins and scraps of lace. When I was little, I loved to check them out and play with buttons. Pretending to be human, I brought them together into families, gave them friends, loves, jealousies and finally conflicts, and at the end of the day I tossed them back to the bottom of the drawer.

I like the monotonous clatter of the sewing machine, the steady rotation of a shimmering silver wheel, and the steady fall of the fabric, but only when my mother is sitting next to it. She has mastered this art to perfection and is the master here. Necks not only for the household members, constantly reworking what they can, but also for our neighbors and townspeople . Years ago, she finished a course for seamstresses in Warsaw and in a small tailor's shop, she gained her first skills under the watchful and strict eye of the owner, Mr. Bauman.

She is a seamstress, a very good seamstress, and she is proud of it. We also do.

Fach in hand

- Mom, why don't you finish it? - Naively and rather without much hope, I am trying to free myself from the hated occupation.

- Honey, you must have a job in hand. - The unfazed mom carefully folds the damp linen cloth she has just been wiping the plates on and sets it on the table.

He repeats this every time I try to argue with her and get out of sewing. Embarrassed, she looks at me intently, as if to penetrate my soul and foretell my future.

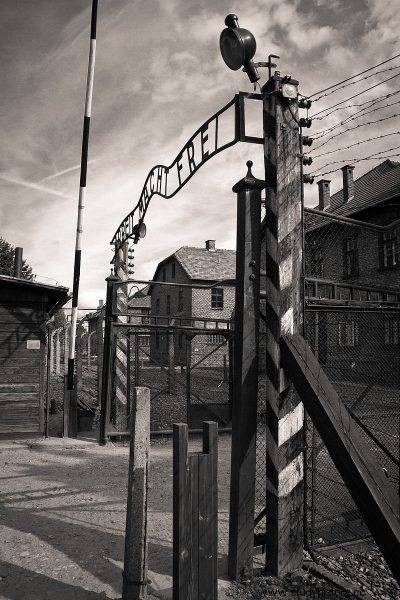

After the war, Mimi and her husband helped establish the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum.

- And I will, because I go to school. - As always, I try to convince her that my grades and commitment can make me earn money in the future by doing what I like, not what I can and honestly hate.

"It's not the same," he says firmly.

- Maybe I will become a teacher or a doctor? You know I have the best grades in my class and I can…

"It's not the same," he insists. - You must be able to do something that people will always need and pay you for . You never know what will come in handy in life, what will happen, and sewing will guarantee you a profit. You must have a job in hand.

- In my opinion, you expect too much of me. - I am puffing more and more and I feel that in a moment, against my will, some unknown force will squeeze tears from my eyes.

“Maybe, but understand that it was the only skill that I found useful here, far from home, in France. Nobody would hire me at school or in the office, I didn't know French.

- Times have changed.

- Not that, I'm afraid.

- My…

"Better show what you screwed up there again." - Mom leans down, brushing a lock of jet black hair across my cheek.

"I don't know what fate has planned"

I can clearly feel the lily of the valley, sweetish aroma of her perfume and I involuntarily close my eyes as if subconsciously I wanted to memorize it. Remember forever.

- Just don't get upset - I warn you. I do not like those moments when he looks at my work, points out mistakes and shortcomings, because I know that he tells me to rip it off, do everything anew, and as always he will say that I am not trying hard enough.

- Well, well, I have to say ... - he says to my surprise, at the same time tugging on the uncut thread. He wraps it around his index finger and, with a quick, firm tug, it breaks off - that I'm pleasantly surprised. Almost perfect.

The text is an excerpt from Nina Majewska-Brown's book "The Last Auschwitz Prisoner", which has just been published by Bellona.

This "almost" is where all my sewing problems begin, but this time, surprisingly, it is different. Mum carefully inspects the hem of the buttonholes, checks that the sleeves of the jacket are even and that the buttons are sewn correctly , and finally, when she puts her knitting back on the table, she looks me straight in the eye.

- Well done, you are ready. If you made a skirt three centimeters longer, it would be perfect. She smiles brightly, a dimple appearing in her cheek. - Mireille, I solemnly declare that you have learned to sew.

- Really?

- Yes, honey, I'm proud of you. - He pats me on the shoulder.

"Promise me that I'll never have to pester the machine again." - On the occasion of the success that has just happened to me, I am trying to free myself from this activity forever.

- I can only promise you that I will not put you next to her. He sighs softly and then adds, "But I don't know what fate has planned.

Escapade to Warsaw

If we only knew then ... Thanks to her persistence, it was sewing, which she forced me to do, which saved me from poverty and hopelessness in later years. It allowed me to earn my bread. For I have become neither a teacher, nor a doctor, or anyone else I dreamed of.

Fate confused everything so that if on that day someone had lifted the veil of secrecy and showed me my world in ten or twenty years, I would not believe it and would simply laugh at it .

- That's good. So I can go? - Excited, not believing in my happiness, I clap my hands together, hoping that she will finally agree.

- To Warsaw? - Mom teases, pretending not to know what I'm talking about.

- You know how I can't wait.

- I know. And yes, you can go.

I fall back to her and squeeze her until she almost loses her breath. My heart is racing and I would like to jump happily like a child, but I don't, for fear that my mother would find it immature and see the little girl in me again, and then withdraw consent to the escapade.

From Polish soil to France

I'm excited. It's the beginning of August 1939 and I'll finally be able to go to the city I've heard so much about, the city my parents miss so much. I will see the Royal Castle, Mermaid, Łazienki with my own eyes, maybe we will even manage to go to Wilanów. Most of all, I will finally meet my family. It is true that I have the impression that I have known them for a long time, in fact forever, because they live every day in the stories of my parents and uncle Stanisław, but in reality I saw my uncles, aunts and cousins only in photos.

My parents moved to Montceau-les-Mines, France in the early 1920s, when I was just two years old. Europe, plowed and exhausted by war, became a melting pot of changes, poverty and crisis, and life guaranteed nothing:neither work, nor stability, nor security, nor hope that things would be fine again. In retrospect, it seems that the parents made the right decision.

Mimi's parents moved to Montceau-les-Mines, France in the early 1920s. Her father became a miner there (illustrative illustration).

My mother, in love with Warsaw, where she was born in 1890 and brought up, where she started her first job in a tailor shop in Saska Kępa, with heartache accepted her husband's idea to leave Poland and look for happiness, and above all work, away from family home. It involved abandoning friends, separation from family, everything she knew and felt safe . Instead, somewhere far away, in a town they hadn't even heard of before, one great uncertainty awaited them.

In addition, she was aware that she was going with a group of children on the way without a return ticket, and fear whispered that she should think carefully and analyze everything again. That maybe the grass just seems greener where there aren't any. In addition, the move was associated with a considerable expense and my mother could not count on the fact that in the event of a failure, just like that, she would simply return home. Of course, her parents would welcome her with open arms, but she also had her ambitions and honor. And most of all, she loved Janek and would not have endured a long separation.

"You don't have to be afraid of me"

They met Jan in Praga. He, tall, strong, swarthy, the life of the party, immediately caught her attention. Then it turned out that he also liked her from the first glimpse. On festive evenings, at the lavishly set table, mum loves to tell in a dreamy voice how dad approached and asked if he could walk her home. How she got scared at first and what a fantastic husband and good man Jan turned out to be.

- It's getting dark, and I'm afraid the neighborhood is not the safest. Perhaps you will let me serve with her arm? My name is Jan Guzik, I am a mechanic and I can assure you that you don't have to be afraid of me.

Intimidated, Karolina did not know what to say. She made an appointment with her cousin, who, however, did not know why she did not come. She knew that there was no one in a dilapidated tenement house in the apartment of her uncle, who had just left for a cousin's funeral in the countryside. After a moment's hesitation, she burned like a cancer put in boiling water and accepted the offer. She even did it with some relief. She did not want to wander alone through suspicious-looking streets, where evil lurked in the gates. At least she thought so. She didn't know this part of town very well, and she only went there with her brothers or parents. Never alone.

In the summer of 1939, Mimi planned to go to Warsaw to meet her relatives (illustrative photo).

- Thank you so much, if it's okay. She held out a cool, slim hand toward him, over which he immediately leaned over and placed a kiss on it. - Karolina Wygnaniec. She did not add that she was Jewish, that she was in the company of a strange man for the first time, nor did she reveal how excited and embarrassed she was by this situation.

It was not a problem for Janek, neither to escort her to the door of the apartment, nor to accompany her on walks around Warsaw in the following days. In fact, in the following weeks he did his best to stay with her as close and as long as possible.

Always gallant, smiling and bursting with humor, he infected her with his optimism and finally made her unable to stop thinking about him. He lived in her head, dreams, desires and dreams. It was with him that she felt safe, beautiful and loved. It was he who gave her the feeling that she was the most important in the world, unique, and at the same time he became the center of her universe.

He was an extraordinary man. Fascinated by technical novelties, he worked as a car mechanic, he also repaired motorbikes and always, despite bathing and cologne, smelled a slight smell of grease. It was, in a way, his trademark and Karolina missed him too. Until the end of her life, it was associated with this wonderful, fleeting whirl in her belly that causes love.

Going for bread

After the wedding, my parents initially moved to a tiny flat in the city center. It was so cramped that it could barely contain a bed and a table with three chairs. Dark, gloomy, with a horrendous rent, it did not predict a better future.

Although Jan's older sister, Paulina, lived nearby, and she helped the young as much as she could, life still seemed to bring challenges that they were unable to cope with. Fortunately, Karolina's parents reached out to overwhelmed spouses. Estera, née Stader, and Bruno Wygnaniec proposed to move to Szymanów, to the old house of Karolina's grandmother, Małgorzata Stader. And although it was not a dream come true, changing the place of residence and moving to a town forty kilometers away from the capital gave hope for an easier life.

The house was a small, here and there a wooden hut covered with moss, the walls of which were covered with clay, white paint peeled off the windows, and storks settled in the crooked chimney in a huge nest, but there was quite a lot of land belonging to it.

They spent a few happy years, but also full of sacrifices, having five children, sons:Zbyszek, Jan Junior, Tolek and Cześek, who unfortunately died just before his first birthday . The last one, in July 1920, was born to me - Mira, to Mimi's friends.

The house grew tighter with each child, and it became more and more difficult to feed such a large group. Mom keeps saying that she breathed a sigh of relief when I was born, because daddy dreamed of his daughter and, to her horror, announced that he would beget children for so long that a girl would appear in their house, as he used to say - the little princess, that is me.

Mimi (first from the left) with new friends, Warsaw 1940

Since I appeared in the world, I have become its treasure, pearl, apple of the eye, sweetness of all worries. And although I am ashamed to admit it and I would not like to offend my mum, because I love her madly, I have an unimaginable love for him and he is the most important in my life. When I was a child, I was waiting for him to return home with his nose stuck to the glass. He was the one who laughed with me the most, tossed me, tickled me and pampered me. Anyway, as the youngest child, I was cherished by everyone:brothers, neighbors, friends.

I cannot imagine how determined my parents were that they decided to leave Poland for bread, and how much courage it must have required of them . The eldest son of the Nowicki family, neighbors living on the outskirts of Szymanów, right on the Pisia River, persuaded his father to take the risk, arguing that it would be better everywhere than here. He himself had been working in France for over a year as a miner and he guaranteed that Janek would find a job in the same mine.

The grandparents were terrified at first and did not want to hear about the idea of the husband of the youngest daughter. Finally, after further deliberations, grandmother's spasmodic crying, despair and doubts, they advised that it would be safer and more cheerful if not one, but two men from the family set out on their way. And that's how it happened. My father said goodbye to my mother, Staszek and aunt Józia, they hugged the children - our four and aunt and uncle two, Stasek Junior and Lila, and ... they set off.

Source:

- The text is an excerpt from Nina Majewska-Brown's book "The Last Auschwitz Prisoner", which has just been published by Bellona.