Impurity can be a lot of trouble. Literally. And although no harmful microbes were known in antiquity, our ancestors realized that something was up. Therefore, they took care of hygiene as much as they could, although some solutions from today's point of view seem very extreme ...

The question of how our ancestors managed in an outhouse or a bathhouse before toilet paper became widely used seems trivial. However, the "threat of feces" in antiquity was very real - and deeply embarrassing. Historians estimate that infections due to poor sanitation and adequate hygiene were even a more common cause of death than continuous wars. Pathologist Philippe Charlier comments:

Treatment of drinking water was a real problem, and nothing was known about the contamination process, nor was any basic hygiene. It used to be better to drink wine and die at forty from cirrhosis of the liver than to drink water and die of typhoid fever under twenty years of age ...

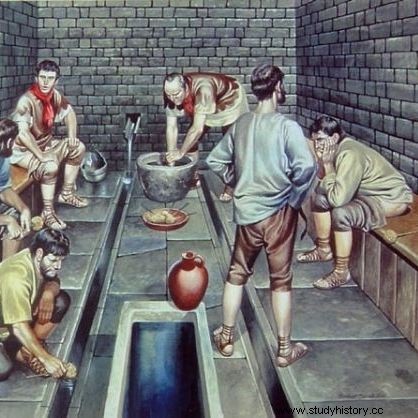

Roman Public Toilets

While there were some ways to remove contaminants from the water - vinegar was used as we do with lettuce today - they often turned out to be insufficient to prevent the absorption of harmful microbes.

Every country is a custom

In terms of access to the civilization novelty, which was toilet paper, the Chinese were the most "ahead" - the original form of this was not there, they started using a breakthrough invention in the 2nd century AD. "Paper with quotes or comments from the Five Classics or the names of the wise men I dare not use for toilet purposes," wrote government official Yan Zhitui 400 years later.

In the West, it took several more centuries to wait for a hygiene revolution, and the first "factory" paper was not launched for sale by the American entrepreneur Joseph Gayetty in the mid-nineteenth century. In the meantime, various methods were used to "threaten with feces", using snow, animal skins, grass, hay, moss, water, and even ... sand and shells - depending on the region and the availability of materials. As a last resort, my own hands were also left.

How did the Romans get on without toilet paper?

So how did the ancient Greeks and Romans deal with this problem? They cannot be denied creativity in this respect. While it was popular to either use a piece of toga or a large leaf, they also developed somewhat more hygienic inventions.

Especially famous is the Roman tersory, i.e. a sponge simply attached to the end of a stick, which was soaked in water before use (under the thresholds of the latrines, small gutters with running water were built). Interestingly, this tool could be dangerous - albeit in a different way than you might imagine. Seneca, in his Moral Letters to Lucylius, described the case of a desperate German gladiator who, tired of fighting, took his own life, stuffing his tersory ... down his throat.

Only for people with strong nerves (and skin)

While rubbing with a wet sponge sounds relatively friendly, the very thought of using the so-called pessoï can give you goosebumps. Why? It was nothing more than roughly hewn pieces of ceramics, which were thrown into the latrine after use or placed in a special container - to be cleaned and reused. Philippe Charlier reports:

They were used throughout the Mediterranean under Roman rule. Their diameter was three to six centimeters, and their thickness was just over one centimeter. The edges of the plates were often smoothed to avoid damage to the skin (hemorrhoids, mucosa irritation, etc.) from frequent use; however, the injuries occurred due to the roughness of the material.

Roman Public Toilets

It is not necessary to have an extremely vivid fantasy to imagine what the consequences were. The famous poet, Horace, comes to the rescue. In the first century B.C. he emphatically described the case of a woman who was too eager to use her pessoï:"to the depths of your skinny buttocks, it smells like cow's catarrh."

The risk was therefore considerable, but the ceramic tiles had other advantages - it happened that their users on the back had the names of their enemies engraved. Rubbing against such a pessoï could actually bring relief - albeit in a slightly different dimension. In Athens and Piraeus, archaeologists found artifacts of this type with the names of, among others Pericles, Themistocles or Socrates. The traces of excrement on them do not leave any doubts as to their purpose ...

Bibliography:

- P. Charlier, What the Dead Teach Us. Pathologist on the trail of the mysteries of history, Esprit 2015.

- Horace, Epody. Satires. Letters, the Library of Polish and Foreign Classics 1980.