The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, unlike the countries of Western Europe, did not participate in the race for overseas colonies, nor did it profit from the slave trade from distant continents. This does not mean, however, that such people did not end up in the country of the Sarmatians. Most often they served as a service and for the then citizens of noble Poland, not used to people with a different skin color, they were a living "curiosity".

There were also visitors from distant countries and continents who achieved high positions and performed important functions, at the same time adopting the culture and customs of Sarmatian Poland as their own.

The Polish word Negro, meaning a black person, comes from the Latin word maurus, which in Roman times and the Middle Ages meant people from northern Africa who had a slightly darker complexion than the Europeans. Although some people now find them offensive, scientists (including Dr. Katarzyna Kłosińska, from the University of Warsaw, who heads the Polish Language Council) emphasize that it is etymologically informative and not offensive. It is emotionally neutral. This is also how the Dictionary of the Polish Language describes them.

The black people came to Poland through trade with the West…

Where did Negroes come from in noble Poland? Of course, as a result of trade with the West, which brought all kinds of riches from the colonies - spices, raw materials, gold. He also earned money from slaves. Many a wealthy magnate, apart from various valuables unknown on the Vistula, also brought Africans from foreign travels. The fate of the blacks in Poland, however, was much better not only than that of slaves in the colonies or in the West, but also the fate of Polish or Ukrainian serfs.

Usually, Negroes ended up on the Vistula River as a service in magnate courts. Of course, the scale of the phenomenon was incomparably smaller than in Western European countries, not to mention North America.

Negro fashion

Among the rich elite of Noble Poland from around the 17th century, it was fashionable to have a black butler, pipe, etc. Having an "international" service was probably a manifestation of a kind of snobbery , and the black man himself, serving for people who are not used to people with a different skin color, was a kind of attraction.

Due to the very high price that had to be paid for a slave from Africa, they were not assigned to heavy work at the courts of the Polish magnates. Usually, they were simply to "decorate" your chambers and were assigned to one function - for example, as a pipe. The African servant was supposed to hand you the pipe at the right moment, and that was where his role ended.

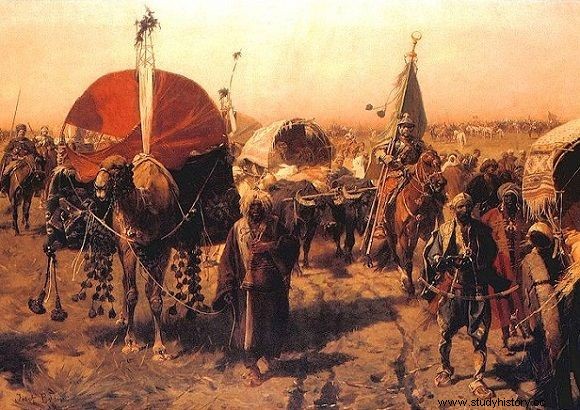

There were quite a few black people in the Commonwealth. The painting "Departure of Jan III and Marysieńka from Wilanów"

It happened that the nobility boasted about their service, which also included Africans. For example, she organized sumptuous processions. Ignacy Krasicki described one of them as follows: “At the carriage:those are going, those are jumping, those are going. A Cossack with a sleeper, a Negro with a quiver, a Tatar with a spear ”.

The retinue of Jerzy Ossoliński, who entered Rome in 1633, is also remembered for its extraordinary splendor. The event was commemorated by the painter Canaletto. From the descriptions of that time, the extraordinary splendor of this delegation emerged, which did not run out of African pages leading the magnificent white steed of the Polish envoy.

African "gentlemen brothers"

Today we know many biographies of Negroes living in noble Poland. Some seem improbable at first glance. For example, the nobleman, castellan of Lviv, Andrzej Fredro, who lived at the beginning of the 17th century, famous for his riotous lifestyle and penchant for sabers, made a servant - a negro, a companion of his excesses. The black companion and Fredro were walking along the streets of the 17th century Przemyśl, wearing a noble's robe with a saber hanging at his belt. Apparently, he could use it quite efficiently. He has supported his master more than once in this regard.

"He took over the local customs and was a saber player, he took an active and outstanding part in his master's brawls," wrote the 19th century historian Władysław Łoziński. Later, Fredro was to free the servant. He got married, had children, grew into Polish culture and customs and carried himself around like the rest of the "gentlemen of the brothers".

Jan III Sobieski highly appreciated his black butler

The black butler was owned by Jan III Sobieski himself. He liked him very much and regretted him greatly after his death. The king's valet - Józef Holender - died at the hands of the Turks during the Battle of Vienna. The desperate king wrote to his Marysieńka:“Almost all the boys died for me. Golanski died of illness one day. The Negro Józef the Dutch, the Turks, already having him in their hands, beheaded him ”. Other kings had African servants, including Stefan Batory.

It happened that a black servant not only gained freedom in Noble Poland, but also achieved honors and high functions. It was like that in the case of Aleksander Dynis - a negro, who was in the service of the bishop of Krakow. He finally married, had children, and became the starost in the village of Koziegłowy in the Siewierszczyzna. On the other hand, an African in the service of the burgrave of Krakow, Jędrzej Czarnecki, was appointed by him a horse, and therefore an official responsible for the stud and court or magnate stables. It was then a very important and prestigious function.

"Blacks of Europe"

When the Republic of Poland fell at the end of the 18th century, it was fought for, among others, by Mulat Władysław Jabłonowski, participant in the Kościuszko Uprising, brigadier general of the Polish Legions. Jabłonowski was brought up in Polish, he felt Polish and identified himself with Poland. He was the illegitimate son of the English aristocrat Maria Franciszka Dealirea, her African butler. He was adopted by the woman's husband, General Konstanty Jabłonowski.

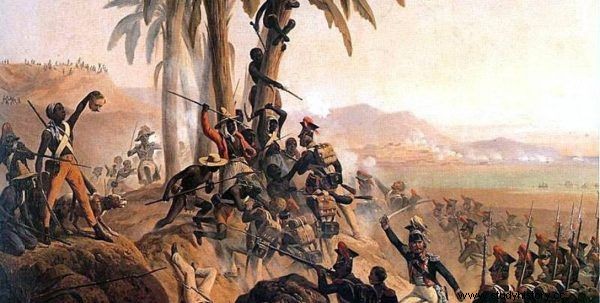

The war route of Władysław Jabłonowski, like the Polish legionnaires, did not bring liberation to the homeland. Instead, they were directed to suppress the rebellion of the Negro and Mulatto people, including slaves, in Haiti, which was then a French colony.

Battle of San Domingo

In this way, Poles were maneuvered into an exceptionally hard war, with an enemy alien to them, in extremely difficult natural and climatic conditions. In addition, the French treated them neglectfully. Not only was there a shortage of people, but also uniforms and food. The soldiers were decimated by epidemics. The fighting in Haiti took a bloody toll. The psychological factor was demobilizing, as Poles were reluctant to take part in their own war, discouraged by the exceptional cruelty to which the French side was going.

At least several dozen Polish deserters sided with the black insurgents. They even belonged to the Dessalines Guard, the leaders of the rebellion. The leader of the rebellion himself used to describe Poles as "the Blacks of Europe". Those who were captured were to be treated better than the French.

It is impossible to confirm how much truth and how much legend in this, but it can be proved by the fact that after the defeat of the Haitian expedition of the French, about 400 Poles remained and settled on the island. They melted into the local Negro community. To this day, there are descendants of Polish legionnaires in Haiti.

"For our freedom and yours"

Probably the greatest Pole representing the ideals of freedom, equality and brotherhood of peoples, regardless of culture or color of skin, was of course the hero of the American Revolution, who fought for "our freedom and yours" - commander Tadeusz Kościuszko.

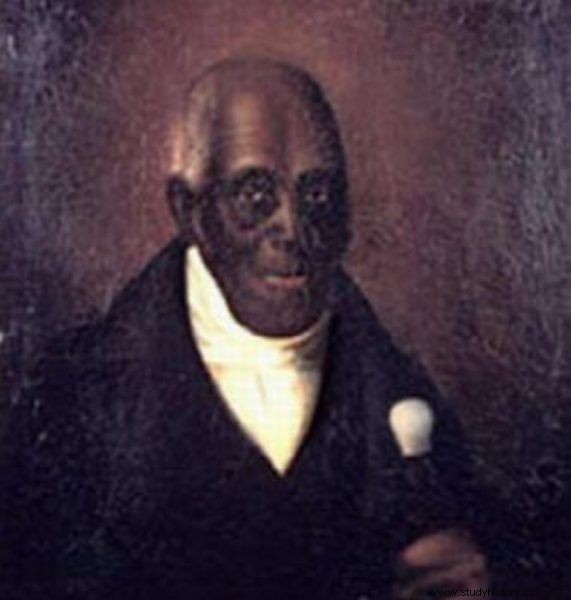

At the time when, at the dawn of the United States, he was building Fort West Point on the Hudson River or fortifying Saratoga, he was accompanied by the black orderly, Agrippa Hull, with whom he was bound by ties of friendship.

Agrippa Hull - the black orderly of Kościuszko

Tomas Jefferson, a friend of Kościuszko and the author of the Declaration of Independence, called the Polish hero "the purest among the sons of freedom". The experiences from his stay in the USA had a great influence on him. Republicans preached freedom and equality for every citizen. Kosciuszko was deeply imbued with these ideas. While in Philadelphia, he met the Indian chief Little Turtle, whom he gave a pistol instructed to use it to fight for the freedom of his people.

He advocated the abolition of slavery, and in Poland - the serfdom of peasants. After winning the Battle of Racławice, he appeared in public in a peasant's russet coat. He proclaimed the Połaniecki Universal, which gave personal freedom to peasants. He announced the complete abolition of serfdom.

When he returned to America in 1798 to collect overdue service money (over $ 18,000), he spent the entire sum on education and freedom for Negroes - incl. from the Jefferson plantation. However, this did not happen. Jefferson did not do his job. For the author of the famous words from the Declaration of Independence, the attitude of the Pole was too radical ... He himself never managed to free the black people working on his plantation.

The chief, who fought for "our freedom and yours", remained faithful to the ideals of freedom until the end. Shortly before his death - in October 1817, he released from serfdom and gave the land to the peasants in his native Siechanowicze, declaring that "servitude is against the law of nature and the welfare of nations".

Bibliography:

- Piotr Antoniewski; "The Negro has done his job, the Negro may leave", that is, the life of black slaves in the Republic of Poland, access:24/06/2020

- Władysław Czapliński:Two Sejms from 1652. A study of the history of the decay of the Polish nobility in the 17th century; Wrocław 1955

- Artur Domosławski, Kapuściński non-fiction, Warsaw 2010

- Marek Gałęzewski; Santo Domingo - an island only for Poles, Germans and blacks, DoRzeczy, 03/05/2017

- Kłopotliwy Murzyn - PWN language clinic, accessed:June 24, 2020

- Tadeusz Korzon:Kościuszko, biography drawn from documents. Krakow, Warsaw, 1894

- Wiktor Malski:The American War of Colonel Kościuszko, KiW, Warsaw 1977

- Riccardo Orizio, Lost White Tribes, Czarne Publishing House, Wołowiec, 2009

- ed. Paweł Średziński, Mamadou Diouf; Africa in Warsaw. The history of the African diaspora on the Vistula, Warsaw 2010

- Alex Storożynski, Kościuszko. Prince of Peasants, Warsaw 2011