Operations performed in the basement rooms that were shaken by bombs exploding all around. Surgical procedures without anesthesia. Sick people lying side by side on the floor. Was it possible to leave the insurgent hospital alive?

Although the outbreak of the uprising on August 1, 1944 surprised many Varsovians, the command of the Home Army had been preparing for the uprising for a long time. The medical services were also included in the preparations. Many hospitals have adequate equipment, drugs, staff and additional space.

Therefore, in the first half of August, the situation in medical facilities was bearable, especially in districts where fierce fighting had not yet started. In Śródmieście, Mokotów or Żoliborz, patients lay on their beds in white, regularly changed bedding, they were also provided with fresh underwear, and doctors organized rounds every day. The first days of the uprising were filled with euphoria and faith in a near victory.

Nobody believed in the announcements of the Germans calling for an end to the fighting. “The microphones are constantly howling theirs:all the houses from which there will be fire will be razed to the ground. Back then, I didn't think they would keep their promise ", recalls Janusz Rola-Szadkowski in the book " With a lightning bolt to the tigers " .

In the first days of August, the mood was full of optimism. Nobody had yet expected that Warsaw would run down with the blood of soldiers and civilians.

With time, the wounded increased. In hospitals, it was becoming more and more crowded. When there were no beds, bunks were pulled out, in the worst of times sacks or piles of newspapers were used as bedding. Two patients were placed on one bunk, the next wounded were placed on the floor, next to the bunks and in the aisles. The nurses and doctors could hardly move in such a tightly filled room, and every wounded person needed care.

“In the halls, screams, groans, eyes glistening with fever, bloody bandages, festering wounds. He lives next to the dying "- such a description of the hospital in Podwale is given by the authors of the book" Hospitals of the Warsaw Uprising ". After the power was cut off, candles and carbide lamps had to suffice. In similar conditions, it is not difficult for an accident, for example a fire, when a candle that replaces a lamp falls over and the bandages start to burn, or the spilled denatured alcohol catches fire.

Only the largest and best equipped facilities had a dynamo - their own light source. The worst conditions prevailed in the hastily organized hospitals. From the book "Hospitals of the Warsaw Uprising" we learn that:

The so-called operating room is a large basement, poorly lit by a few candles. The entire equipment consists of two regular tables, a few chairs, stools and a soft armchair.

The article was based, among others, on the memoirs of Janusz Rola-Szadkowski entitled "With Błyskawica na Tygrysy" (Poznań Publishing House 2017).

Worst of all, however, was the lack of enough doctors and medical personnel to look after the sea of the wounded. Several-year-old nurses and the families of the sick helped in taking care of the wounded. The medics worked tirelessly.

Underground hospitals

Doctor Cyprian Sadkowski "Skiba", who was taken to the hospital at the "Krzywa Lantern" in the Old Town, noted in his memoirs:

P to lay down as sick, which in our circumstances is tantamount to death. Injections are not made, because there is nothing to boil the syringes. Gas gangrene kills almost every wounded person .

The doctor, wounded twice, was in the hospital with pneumonia. He shared the mattress with the former Polish ambassador to Moscow. His companion died three days later, Sadkowski had to wait several hours for the nurses to take the corpse.

When bombs fell on the city, life went underground. The soldiers wandered through the sewers. Hospitals were organized in cellars and shelters.

When house after house was collapsing in the Old Town, many parts of Śródmieście were still relatively calm. In September, there were no longer any safe districts. Bombs fell on the city regularly. Life went underground. Civilians camped in the cellars of tenement houses, liaison officers who carried reports often sneaked past, soldiers wandered from place to place, going through the sewers.

Hospitals also organized halls in shelters and cellars. During the raid, the sick were counting the bomb strikes in suspense. They listened to the roar of the falling walls and gasped for air in the dust. After the raid, the nurses handed out gauze and cotton swabs soaked in water to facilitate breathing. In overcrowded facilities, mildly injured patients were placed in rooms on the ground or first floor, but accidents were frequent there, as glass and window frames were flying out during air raids.

Amputation is everyday life

“If possible, call a surgeon's consultant before performing the amputation”, such a recommendation was issued by the office of the sanitary chief of Śródmieście Północ. Under normal circumstances, limb amputation is a last resort, during the Warsaw Uprising it was almost a routine procedure.

There were no tools and medications to save a wounded arm or leg, so the only option was to cut. Teresa Bojarska "Klamerka", a nurse from the "Baszta" regiment, was shot twice in the leg. Unable to walk, she spent several hours lying on the grass until she was finally transported to the hospital.

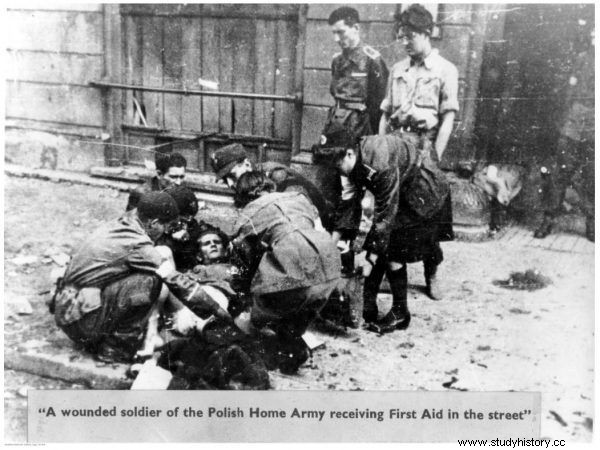

First aid was given to the wounded still on the street. Often under fire.

The wound was terribly dirty. The doctor treated his leg for several hours, removing pieces of grass, pebbles and other debris. The "Clamp" was in danger of being amputated. The leg was saved because the paramedic commander obtained a tetanus vaccine somewhere, which was missing in the hospital.

Wanda Okolska-Woltanowska "Mrówka", a liaison officer shot in the street when she was running with a report, was less lucky. The wounded woman was taken to an improvised hospital point in the basement. Doctors did not have penicillin, and gangrene was developing in the leg. The decision was made to amputate.

The girl was prepared for a heroic death, but not for becoming an invalid. At the time of the uprising, she was only 16 years old. Even before the operation, her friend, Jadwiga Chuchla, "Pszczółka", visited her in the hospital. When she went down to the basement to bring the sick woman water, she saw a gruesome sight - there were severed arms and legs that had not yet been removed by the staff.

The article was based, among others, on the memoirs of Janusz Rola-Szadkowski entitled "With Błyskawica na Tygrysy" (Poznań Publishing House 2017).

"Amputations have become commonplace," says nurse "Dora" from one of the hospitals in Żoliborz, the heroine of the book "Girls from the Uprising". She remembered the first operation of this type she assisted forever. Doctors told her to hold a trimmed leg, she saw skin cuts, muscles and bone sawing up close.

After the end of the procedure, the shocked nurse was still standing, holding the severed limb, not knowing what to do with it. Sometimes, paradoxically, the lack of amputation tools worked to the benefit of the wounded. When the doctors had nothing to cut, they had to make various attempts to treat gangrene - this is what happened in the case of a certain female liaison officer, whose fragment of a bomb cut her leg and ankle.

"Sew, I'll hold on!"

The longer the uprising lasted, the worse it was in the hospitals. Many of them lacked not only places and medicines, but even water, light, blankets on which to lay patients or cover the dead. There were more and more injured people - from the front lines, from bombings and fires. No one was denied help, but the drugs for sleep and pain were running out.

Anna Jakubowska "Paulinka", a nurse, assisted in the head wound stitching procedure. The patient, a medical student, aware of her serious condition, consoled the doctor, "Sew, I can stand it". The paramedic held a candle to illuminate the wound, and the doctor performed the procedure without the use of anesthesia. Ether, necessary for anesthesia, was priceless during the uprising.

Teenage girls showed courage in the sanitary patrols of the Military Women's Service. The photo shows a Home Army nurse at 9 Moniuszki Street, August 5, 1944.

For one ampoule of a drug, for example opium, morphine, pantopone, which were used to relieve pain, you could get two bottles of vodka in Śródmieście. Live operations required special involvement on the part of nurses, they had to hold the patient struggling with pain and tearing.

Maria Zatryb-Baranowska from the hospital in Powiśle hardly fainted during the procedure of digging up the fragments from the soldier's torn hand. The wound was rotten and the rotten body exuded a terrible stench, the nurse turned pale and felt nauseous, then the operating doctor threw insults at her - as he later explained, he saved her from fainting.

In the Sano Hospital at 13 Lwowska Street, even such serious procedures as trepanation of the skull were performed without sleep, the wounded from pain lost consciousness. The surgeons also had to be creative to compensate for the lack of professional tools - a spoon that was borrowed from the kitchen was used to remove blood from the abdominal wounds.

At the end of the Uprising, when Warsaw was on fire, people operated without anesthesia with kitchen knives and ordinary saws.

The situation outside the hospital building also made work difficult, when, for example, a massive German shelling in the street made the room vibrate. When it was not possible to transport the wounded to the hospital, there were operations in poorly equipped sanitary facilities, which were mainly used to provide emergency care.

Then, the operation was performed with a kitchen knife and a ball disinfected with alcohol, and the patient was anesthetized with morphine. Monika Żeromska, a nurse from the hospital in Długa Street, recalled that at one point in her facility only cotton wool, plasters and oil ointment were left in her facility.

Lead-colored human hulls

After major bombing or shelling, numerous groups of wounded in various conditions were sent to hospitals. A nurse from the hospital "Terminus" described the cases of the wounded from the explosion of shells from salvo mortars:"Naked human hulls the color of lead were brought into the hall from the top of the head to the fingernails on the limbs." In such patients, only tannin solution compresses and pain relievers were used. There was nothing else that could be done for them.

Infectious diseases were spreading in hospitals due to poor sanitary conditions. Dysentery was particularly troublesome. In the absence of drugs, malnutrition and general weakness of the organism, this disease could be life-threatening. Various preventive measures were therefore tried, for example, wounded soldiers were given 50 grams of alcohol a day.

The Uprising was also defeated by thousands of victims, wounded and killed, among the civilian population.

The alcohol came from the jars that held the specimens, such as the heart or kidneys, needed to study anatomy. The soldiers called the "cure" liverwort or cockle and were glad that it did its job and was effective in protecting against dysentery.

In some hospitals it was not possible to prevent this disease, and there were no conditions for creating a separate room for the wounded and those suffering from dysentery. “People with stuffiness were lying on the pallets, the wounded next to those suffering from bloody diarrhea. There was a lack of everything, ”we read in“ Warsaw Uprising Hospitals ”.

Death in insurgent hospitals lurked at every step. She did not spare anyone, not even the doctors who, apart from the hours, could spend up to two days on duty without a break. It happened that the facility was regularly fired upon and the bullet reached the doctor during the morning round. In one of the downtown hospitals, an incendiary missile fell into the room, the doctor who was treating the injured person started to burn, and the patient fell off the table.

Bibliography:

- Patrycja Bukalska, August girls , Trio Publishing House, Warsaw 2013.

- Anna Herbich, Girls from the Uprising , Znak Horyzont, Krakow 2014.

- Janusz Rola-Szadkowski, With lightning on the tigers. Insurgent's diary , Poznań Publishing House, Poznań 2017.

- Bożena Urbanek, Nurses and nurses in the Warsaw Uprising 1944 , Państwowe Wydawnictwa Naukowe, Warsaw 1988.

- Maria Wiśniewska, Małgorzata Sikorska, Warsaw Uprising Hospitals , Oficyna Wydawnicza Rytm, Warsaw 1991.

- Maria Zatryb-Baranowska, Uliczka Powstańców , Foundation of the Warsaw Field Hospitals, Warsaw 2014.