We wrote before that the stories about pirates of the Caribbean are a myth. The true golden age of piracy was over 1,500 years earlier:at the end of the Roman republic. At that time, sea robbers established their own states, kidnapped tens of thousands of people and threatened the existence of the Eternal City.

Pirates were undoubtedly one of the greatest plagues of antiquity. The sea robber of antiquity, however, had little to do with the romantic swashbuckler known from modern movies. He was not always a ruthless robber who took pleasure in the suffering he inflicted on people. The truth about ancient pirates is much more complex.

Pirate, or who?

In ancient times, pirates were adventurers who tried to live independently of the authorities, occupying small islands and ports, and invading neighboring territories. They also included people who would later be called corsairs, and representatives of entire tribes and communities.

Gaius Werres was so brash that he even looted the Temple of Juno in Malta. Today only inconspicuous ruins remain (photo:Frank Vincentz, CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Ligurians, Cilicians and Illyrians, living in barren, mountainous areas, often engaged in maritime robbery, which served the Romans as an excuse to conquer entire areas as was the case with Crete or the Balearic Islands.

Well-born people were also active in piracy. Among them, we can mention Gaius Werres, he used his authority as a legate and proconsul to plunder the territories under his control. His accuser was Cicero, who in the preserved speeches directly calls him a pirate.

Werres plundered the temple of Juno, which the other pirates near the base did not dare to touch . In turn, he was to hide the captured pirates, and after receiving a bribe, release them, seemingly condemning other unfortunates to death.

Merchants and highwaymen

Of course, pirates most often lived off loot. However, its natural corollary is sea trade the robbers were therefore also merchants . Inhabitants of port centers often did business with them as they did with anyone selling the spoils of war, and the status of a pirate trading city provided at least an appearance of security.

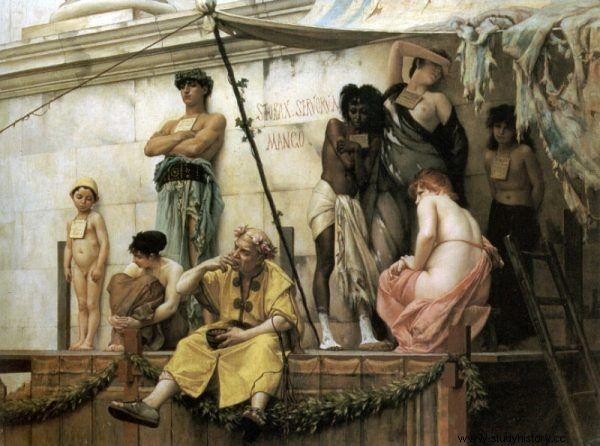

In addition to animals and luxury items, people were also a commodity, and pirate raids were often aimed at capturing slaves. Not only people who were free so far, but also those who were already owned by others, were kidnapped, thus feeding the secondary market.

One day you are a happy citizen of the Greek policy, the next you land as a commodity at the slave market ... (painting by Gustave Boulanger).

Thanks to the Romans, trade in living goods flourished. The conquerors from the Tiber bought a lot and without scruples, also Greek citizens poleis . The market on the island of Delos experienced a special boom. Up to 10,000 slaves a day would pass through the port there .

Pre-AD kidnappers and terrorists

A typical pirate activity was to kidnap people for ransom, as is happening today off the coast of Somalia . This eliminated the embarrassing necessity of visiting the slave market, and the families of the captured were often willing to pay more than regular customers interested in live goods.

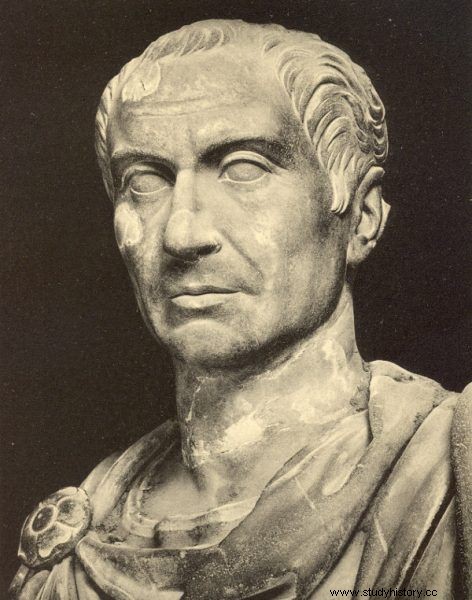

The most famous victim of pirate audacity was the young Julius Caesar. Interestingly, when they demanded a ransom of 20 talents, he himself demanded that it be increased to 50 talents .

The future conqueror of Gaul spent 40 days as a prisoner. He was probably treated well, but he constantly threatened to kill the robbers who were imprisoning him. He did it like a joke, but it turned out that he did not throw words into the wind. After his release, he assembled the fleet, captured his captors and ordered their execution.

Julius Caesar is probably the most famous "victim" of ancient pirates (photo:public domain).

Pirates sometimes acted almost like modern terrorists. In the 3rd century BC they abducted some of the inhabitants of the city of Teos, including women and children, and demanded a ransom of 10% of all their property from the remaining citizens. They gave the attacked 23 days to collect the amount, and all this time there was a special pirate delegation in the city to "help" in estimating the property and make sure the total amount is collected.

Unexpected effects of the conquests

The expansion of Rome weakened and destabilized the existing sea powers. A vacuum was created that the Romans did not intend to fill initially. They were not directly affected by the problem and, moreover, they themselves benefited from trading with pirates. As a result of this passivity, a piracy nest was created in Cilicia in southern Asia Minor.

In the 40s of the 2nd century, a certain Tryphon established a pirate fleet base in this mountainous country. The Seleucid rulers of the eastern Mediterranean could not get rid of it, because the peace treaty imposed on them by the Romans excluded this area from their sphere of influence. However, these areas were an excellent base against the rich coasts of Syria.

Pirates Lords of the Sea

Tryphon was finally defeated, but following his example, other pirates carved out small states that took advantage of the situation in the region. And the rank of these robbers is evidenced by the fact that the ancients called them tyrants , archpirates or even kings .

Roman galley model (photo:Rama, CC BY-SA 2.0 FR).

In the first century BC piracy has become a real scourge . According to the ancient historian Plutarch, at the height of their power, the sea robbers were to sack 13 sanctuaries and capture 400 cities. Cicero mentions that among the gains was the island of Delos, which was previously a trading port for pirates. Appian even claims that they have taken over the entire Mediterranean.

Pirates were also served by an alliance with Rome's enemies, such as the king of Pontus Mithridates or the rebel Sertorius. Italy itself was under threat. Cassius Dio reports that pirates have invaded the port of Ostia, located just 17 km from Rome and destroyed the fleet there.

According to Cicero: not only are we banned from the provinces, we are kept away from the shores of Italy and its ports, but we are even banned from the Via Appia! Plutarch adds: Their power was felt in all regions of the Mediterranean, so it was impossible to sail anywhere, and trade died out .

Great Pirate Hunt

Actions against pirates were undertaken by various chiefs, incl. Antoniusz Retor, Lukullus or Murena. However, these were temporary and insufficient measures, so Pompey the Great was entrusted with the task of the final solution of the problem. In 67 B.C.E. he was given a three-year office with almost unlimited budgets and recruitment, and the right to intervene in all provinces up to 50 miles inland.

Even the port in Ostia, located near Rome, was plundered by impudent pirates (photo:Pudelek, CC BY-SA 3.0).

Pompey divided the sea into 13 regions and gathered troops in each of them so that he could pursue the bandits from all sides at the same time. The purpose of the operation was both to protect sea routes and to attack pirates in their bases. The grain shipments to Rome were restored within 40 days and in 49 others the pirates pushed to Cilicia were defeated.

Pompey was supposed to succeed because he saw that the cause of piracy was poverty. Instead of mass executions, he pardoned many highwaymen and decided to move the pirates from sea to land and let them experience a fair and innocent life by living in cities and farming the land (Plutarch).

What father, such son?

It is difficult to assess to what extent Pompey's actions brought a long-term improvement, and to what extent it was a propaganda success. It is worth mentioning, however, that one of the last pirates of the republic was none other than Pompey's son, Sextus . Although he did not participate in the assassination of Caesar, he was one of the victims of proscription.

In order to avoid death, he set up a strong base on his controlled Sicily, where Caesar's other enemies, but also adventurers and escaped slaves found shelter. For years, the waters around Sicily were under the control of Pompey, and as a result of his actions hunger in Rome because sailors on merchant ships from the east were afraid when they sailed through Pompey and his forces in Sicily (Appian).

When Octavian Augustus finally dealt with Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium, he could also deal with Sextus Pompey (a painting by Lorenzo A. Castro in the illustration).

Although Pompey was a rebel rather than a pirate, and a man liked in Rome, the propaganda of the victorious Octavian Augustus made sure that he went down in history as a pirate.

Pax romana at sea

In the first centuries of the empire, piracy ceased to be a pressing problem. It did not completely disappear, but it was mainly found in the borderlands. Strabo writes about the inhabitants of the Black Sea coast who organized plundering expeditions on small ships that could fit 25 people. In the time of Claudius, it was necessary to intervene in Cilicia again.

These were local problems, not a threat that would affect the entire country. According to Suetonius, the inhabitants of the empire were to thank Octavian for that they live thanks to him, thanks to him they sail the seas, enjoy freedom and prosperity .

Bibliography:

- Appian of Alexandria, Roman history , vol. 3, translated, edited and introduced by Ludwik Piotrowicz, Ossolineum-DeAgostini, Wrocław-Warsaw 2004.

- A. Avidov, Were the Cilicians a Nation of Pirates? Mediterranean Historical Review, vol. 10 (1997), pp. 5-55.

- David C. Braund, Piracy under the Principate and the Ideology of Imperial Eradication , [in:] War and society in the Roman world , ed. by John Rich, Graham Shipley, Routledge, London 1993, pp. 195-212.

- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, Lives of the Caesars , vol. 1, translation, introduction and commentary by Janina Nimerska-Pliszczyńska, preface Józef Wolski, Ossolineum-DeAgostini, Wrocław-Warsaw 2004.

- Juliusz Jundziłł, Romans and the sea , Ed. University of Pedagogical University, Bydgoszcz 1991.

- Cassius Dion Kokcejanus, Roman history , translated and edited by Władysław Madyda, with a historical introduction by Iza Bieżuńska-Małowist, Ossolineum-DeAgostini, Wrocław-Warsaw 2005.

- Arthur Keaveney, Lukullus , PIW, Warsaw 1998.

- Marek Tulliusz Cicero, Speeches , translated by Stanisław Kołodziejczyk, Julia Mrukówna, Danuta Turkowska, Antyk, Kęty 1998.

- Plutarch of Cheronea, Lives of Famous Men (from Parallel Lives) , vol. 3, translated and commented on by Mieczysław Brożek, Ossolineum-DeAgostini, Wrocław-Warsaw 2006.

- Publius Cornelius Tacitus, Works , translated from Latin by Seweryn Hammer, Czytelnik, Warsaw 2004.

- Luke Schreiber, Sulla 138-78 BCE , Inforteditions, Zabrze – Tarnowskie Góry 2013.

- Philip de Souza, Pirates in the Greco-Roman World , Replika, Zakrzewo 2008.

- Titus Livius, The history of Rome since the foundation of the City , vol. 4, translated and edited by Mieczysław Brożek, commentary by Mieczysław Brożek, Józef Wolski, Ossolineum, Wrocław-Warsaw-Kraków-Gdańsk 1982.