Page 1 of 7

January 22, 1879, almighty Victorian England wiped out, at the foot of a mountain in South Africa , one of the most complete and humiliating military defeats of its history during the Battle of Isandlwana . The British counterpart of what the Battle of the Little Bighorn was to the United States of America, this defeat was inflicted on a United Kingdom sure of its strength and superiority by warriors armed mostly with spears and hide shields beasts:the Zulus. In the aftermath of Nelson Mandela's death, a look back at a South African history marked by migrations and clashes.

January 22, 1879, almighty Victorian England wiped out, at the foot of a mountain in South Africa , one of the most complete and humiliating military defeats of its history during the Battle of Isandlwana . The British counterpart of what the Battle of the Little Bighorn was to the United States of America, this defeat was inflicted on a United Kingdom sure of its strength and superiority by warriors armed mostly with spears and hide shields beasts:the Zulus. In the aftermath of Nelson Mandela's death, a look back at a South African history marked by migrations and clashes.

South Africa, a troubled land

At the beginning of the XIX th century, what is now South Africa experiences an unprecedented wave of upheavals, which will plunge it into turmoil. It was then populated by a multitude of ethnic groups, today classified into two main groups according to their linguistic affiliation:the Khoisans in the west (whose main ethnic group, the Khoikhoi, are related to the Bushmen of Namibia), and the Bantus in the east. The latter, whose linguistic family extends over the entire southern half of the African continent, are themselves divided into subfamilies, of which the two main ones, in South Africa, are the Ngunis on the one hand, and the Sothos -Tswanas on the other hand. These linguistic groups are in no way state entities, and are fragmented into numerous clans and tribes with no "national" identity.

These peoples were no longer alone on South African soil. In 1653, the Dutch East India Company established, near the Cape of Good Hope, a supply base for its ships en route to the Dutch trading posts in India. This establishment was to become the city of Cape Town, then the colony of the same name. Its European settlement was accelerated by many French Calvinists after Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Preferring to go into exile so as not to renounce their faith, these Protestants took refuge for many in the Netherlands, and some are added to the Dutch who leave to settle in the colony. First concentrated along the coast, these “Cape Dutch” gradually subjugated the Khoikhoïs and penetrated inland. They established farms there (hence their nickname of Boers, “farmers” in Dutch) exploited thanks to the Khoikhoi workforce, and to Malay slaves brought in large numbers from the Dutch Indies. Some of them, the "itinerant Boers" (Trekboers ) practice a semi-nomadic pastoralism which leads them to extend the Cape colony ever further east. They end up entering into repeated conflicts there with a major group of Nguni tribes, the Xhosas.

In 1795, the Cape colony was overtaken by the repercussions of the French Revolution. While the Netherlands was conquered by the French armies and transformed into a Batavian Republic subservient to France, the English retaliated by occupying the colony. When the Treaty of Amiens put an end to the Wars of the Second Coalition in 1802, Great Britain returned the Cape to the Dutch. The peace, however, did not last, and hostilities resumed the following year. South Africa remained out of the conflict until a British army conquered Cape Colony again in 1806. This occupation turned into annexation pure and simple in 1814, when Great Britain and the Kingdom of the Netherlands, created after the defeat of Napoleon I

st

, sign the London Convention.

In 1795, the Cape colony was overtaken by the repercussions of the French Revolution. While the Netherlands was conquered by the French armies and transformed into a Batavian Republic subservient to France, the English retaliated by occupying the colony. When the Treaty of Amiens put an end to the Wars of the Second Coalition in 1802, Great Britain returned the Cape to the Dutch. The peace, however, did not last, and hostilities resumed the following year. South Africa remained out of the conflict until a British army conquered Cape Colony again in 1806. This occupation turned into annexation pure and simple in 1814, when Great Britain and the Kingdom of the Netherlands, created after the defeat of Napoleon I

st

, sign the London Convention.

Far further east, the Bantu peoples of South Africa are also experiencing their share of upheavals. Dingiswayo's rise to the head of the Mthethwas, an Nguni tribe, does not yet mark a real break with the tribal system, but initiates a decisive turning point in the country's history. Using in turn force and diplomacy, Dingiswayo manages to establish a form of hegemony over the neighboring clans. This confederation, still very informal, notably includes the Zulu tribe in its ranks. One of them, Shaka , proves to be one of Dingiswayo's most loyal and effective lieutenants, and the latter helps him take control of the Zulu tribe. The Mthethwa hegemony however clashed with another Nguni tribe, the Ndwandwe, and Dingiswayo was killed confronting them, probably around 1817. The struggle continued between Shaka, who claimed Dingiswayo's heritage, and the chief of the Ndwandwe, Zwide .

Shaka, the Warrior King

During his years in the service of Dingiswayo, Shaka designed a whole series of reforms that he will be able to fully develop after the death of his mentor, transforming in less than ten years what was at best a vague tribal confederation into a powerful centralized kingdom. The scope of these reforms, analyzed by Western historians, often places Shaka among the greatest military geniuses in history, and the Zulu leader is sometimes nicknamed the "Black Napoleon" because of both his contemporaneity with the Emperor of the French and the extent of his military reforms and his conquests, but also of the completely new philosophy of war which was his. Given the sporadic character of Zulu contacts with, on the one hand, the Portuguese of Mozambique in the northeast, and on the other, the Dutch and the British of the Cape Colony in the west, the influence of ideas Western ones is probably to be ruled out. So that we will rather speak here of "evolutionary convergence", to use a concept in vogue in biology.

During his years in the service of Dingiswayo, Shaka designed a whole series of reforms that he will be able to fully develop after the death of his mentor, transforming in less than ten years what was at best a vague tribal confederation into a powerful centralized kingdom. The scope of these reforms, analyzed by Western historians, often places Shaka among the greatest military geniuses in history, and the Zulu leader is sometimes nicknamed the "Black Napoleon" because of both his contemporaneity with the Emperor of the French and the extent of his military reforms and his conquests, but also of the completely new philosophy of war which was his. Given the sporadic character of Zulu contacts with, on the one hand, the Portuguese of Mozambique in the northeast, and on the other, the Dutch and the British of the Cape Colony in the west, the influence of ideas Western ones is probably to be ruled out. So that we will rather speak here of "evolutionary convergence", to use a concept in vogue in biology.

Warfare was fairly common among the Ngunis, but its impact was minimal. It took the classic form of tribal or “prehistoric” armed conflicts, such as they have been observed by ethnologists in Amazonia or Papua. The battles resulted in ritualized confrontations limited to exchanges of javelins, during which close combat was rare and human casualties low. In the pastoral societies that were the Bantu tribes of South Africa, the main sources of contention were over cattle and pasture, and the most extreme form of armed conflict was the raid to seize the first or drive out an intruder. of the seconds. The concepts of decisive battle or total victory, as sought by Napoleon Bonaparte in Europe at the same time, were completely unknown to the Bantu tribes. Within the Bantu tribal organization, men were traditionally grouped by age class , in a manner quite similar to that employed in Europe for conscription. Each age group (intanga ) was indebted to the chief of the clan or tribe for a kind of drudgery taking various forms, within which warlike expeditions were only one occupation among others.

Shaka hijacked this tradition for his own purposes. Each intanga became a regiment (ibutho , plural amabutho ) used exclusively for military purposes. Furthermore, its members no longer swore allegiance to their respective chieftains, but to Shaka alone, so that all men of the same age class belonging to the tribes under Shaka's control became part of a single regiment - favoring the emergence of a Zulu identity. In doing so, Shaka effectively transformed the intanga in the military conscription system . Each ibutho had to build his own kraal (an Afrikaner word to be compared to "corral", and which designates both a cattle pen and a village), where he was to reside until Shaka authorized the members to marry. In the meantime, the regiment was actively serving in the impi , the word Zulu being used to designate any army, whatever its size. Even when married and settled in their own domain, members of an ibutho remained at Shaka's disposal in case of need, and had to return regularly to their kraal regimental to train there.

Shaka hijacked this tradition for his own purposes. Each intanga became a regiment (ibutho , plural amabutho ) used exclusively for military purposes. Furthermore, its members no longer swore allegiance to their respective chieftains, but to Shaka alone, so that all men of the same age class belonging to the tribes under Shaka's control became part of a single regiment - favoring the emergence of a Zulu identity. In doing so, Shaka effectively transformed the intanga in the military conscription system . Each ibutho had to build his own kraal (an Afrikaner word to be compared to "corral", and which designates both a cattle pen and a village), where he was to reside until Shaka authorized the members to marry. In the meantime, the regiment was actively serving in the impi , the word Zulu being used to designate any army, whatever its size. Even when married and settled in their own domain, members of an ibutho remained at Shaka's disposal in case of need, and had to return regularly to their kraal regimental to train there.

Shaka's reforms also extended to the field of armament . Until then, the Zulu warrior was equipped with javelins (ipapa ), a light cowhide shield, and a truncheon (iwisa ) for close combat. Believing that the best way to achieve victory was to aggressively pursue melee engagement as soon as possible, Shaka modified this panoply to suit him best. The spearhead was lengthened – up to 25 or 30 centimeters – and widened, and its handle considerably shortened. The resulting short spear, dubbed iklwa in Zulu and incorrectly called assegaï (“sagaie”) by the Europeans, was used more like a sword than a spear. It was forbidden to use it as a throwing weapon, on pain of death; a few ordinary javelins were thrown before the charge. The shield was also enlarged, so that it could be used to deflect the opponent's shield:the warrior then only had to stab him with his iklwa . The shield was the only body protection, to the exclusion of any other form of armour. The Zulu warriors generally went into battle wearing only a loincloth, the ornaments, specific to each regiment, being reserved for ceremonies. To strike his enemies quickly, Shaka wanted his army to be as mobile as possible. His warriors therefore traveled light, a herd ensuring the supply of food. For the same reason, the wearing of sandals was forbidden, as Shaka felt that they slowed down their wearer. The baggage of the Zulu army was reduced to the strict minimum. They were carried by porters (udibi ), children and adolescents who, too young to be enrolled in the amabutho , were nevertheless subject to a class system from the age of six.

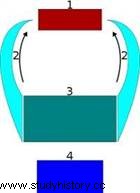

Thus organized and equipped, the Zulus transformed traditional Bantu warfare into a brief, decisive, and deadly confrontation. Shaka added his talents as a tactician, creating a stereotypical battle plan remained known as the "horns of the buffalo". The center of the army (the "chest" of the buffalo) launched an attack intended to fix the enemy formation. Two wings (the "horns" proper), generally made up of the youngest regiments, then took advantage of their mobility to attack the flanks of the adversary, then tried to encircle him by joining behind him. If this tactic was slow to produce a decisive result, a reserve (the "rump" of the buffalo), formed by the most seasoned regiments, could intervene. The “buffalo horns” are really nothing more than the Zulu version of the “four F” principle that forms the basis of contemporary infantry combat:find (find), fix (fix), flank (flank), finish (destroy). Each ibutho was commanded by one or more izinDuna (singular inDuna , literally “chief”), several amabutho being likely to be grouped into "corps" (the different parts of the "buffalo") within the same army. The main weakness of this tactical structure was the absence of intermediate officers between the warriors and their izinDuna , which made the regiment extremely difficult to control once the engagement began.

Thus organized and equipped, the Zulus transformed traditional Bantu warfare into a brief, decisive, and deadly confrontation. Shaka added his talents as a tactician, creating a stereotypical battle plan remained known as the "horns of the buffalo". The center of the army (the "chest" of the buffalo) launched an attack intended to fix the enemy formation. Two wings (the "horns" proper), generally made up of the youngest regiments, then took advantage of their mobility to attack the flanks of the adversary, then tried to encircle him by joining behind him. If this tactic was slow to produce a decisive result, a reserve (the "rump" of the buffalo), formed by the most seasoned regiments, could intervene. The “buffalo horns” are really nothing more than the Zulu version of the “four F” principle that forms the basis of contemporary infantry combat:find (find), fix (fix), flank (flank), finish (destroy). Each ibutho was commanded by one or more izinDuna (singular inDuna , literally “chief”), several amabutho being likely to be grouped into "corps" (the different parts of the "buffalo") within the same army. The main weakness of this tactical structure was the absence of intermediate officers between the warriors and their izinDuna , which made the regiment extremely difficult to control once the engagement began.

Rise of the Zulu Kingdom

Experienced under the patronage of Dingiswayo, Shaka's reforms soon revealed their full potential in the war being waged for his succession. To the more numerous Ndwandwés, the Zulus oppose their technical and tactical superiority. Shaka weakens his adversary after a first major battle around 1818, but the struggle continues. Eventually, he won the long-sought decisive victory on the Mhlatuze River. In 1820, Zwide and the Ndwandwés had to flee their territory, because not content with having defeated them, the Zulus settled there. Shaka thus inaugurates a cycle of conquests which will last until his death. The neighbors of the Zulus must submit:those who resist are invariably crushed by the Zulu war machine after bloody battles, and must leave their lands to escape annihilation. Ultimately, Shaka becomes sole ruler of a kingdom of more than 30,000 square kilometers.

In doing so, the Zulu king also opens Pandora's box. Populations fleeing the Zulu conquests had to settle in new territories, from which they in turn drove out the previous occupants. A chain reaction is spreading through South Africa. The situation was further aggravated when certain tribes in turn adopted Zulu organization and tactics. Thus, the Ndebeles – called Matabélés by the British – turned against Shaka after having been his allies; defeated, they flee north, where they spread further chaos and eventually establish their own kingdom. Others federate to constitute similar States, in order to resist the invaders. The region's fragile pastoral economies are devastated, and mortality is skyrocketing. The chaos unleashed by the Zulu conquests will go down in South African history as Mfecane , “the Dispersion” in Zulu. The number of Mfecane victims is impossible to determine, but some do not hesitate to estimate it in millions.

Summary map of migrations from Mfecane:the conquests of the Zulus (in black) and the Ndebeles (in brown) lead to the massive displacement of the other tribes of the Ngunis (in green) and the Sothos-Tswanas (in pink).

The reasons for this war frenzy remain obscure. It is obvious that Shaka's reforms and his total victories generated a deadly imbalance within a civilization that had operated on a tribal mode and a limited vision of warfare for centuries. The scarcity of contemporary written sources of Shaka – the Zulu culture being essentially oral – hardly allows us to question the motivations of his expansionist aims. It is certain, however, that he only continued, by developing it, the search for power which was already that of his mentor Dingiswayo. In addition, South Africa was under strong demographic pressure at that time. , contacts with white settlers having taught its inhabitants the cultivation of corn. More and more herds, fields and pastures were therefore needed to feed the growing population of the kingdom and maintain the amabutho to the ever-growing ranks of Shaka. Pressure from the Cape Colony, which continued to expand eastward, and the actions of the Portuguese, who continued to trade in slaves from nearby Mozambique, were undoubtedly additional factors.

The reasons for this war frenzy remain obscure. It is obvious that Shaka's reforms and his total victories generated a deadly imbalance within a civilization that had operated on a tribal mode and a limited vision of warfare for centuries. The scarcity of contemporary written sources of Shaka – the Zulu culture being essentially oral – hardly allows us to question the motivations of his expansionist aims. It is certain, however, that he only continued, by developing it, the search for power which was already that of his mentor Dingiswayo. In addition, South Africa was under strong demographic pressure at that time. , contacts with white settlers having taught its inhabitants the cultivation of corn. More and more herds, fields and pastures were therefore needed to feed the growing population of the kingdom and maintain the amabutho to the ever-growing ranks of Shaka. Pressure from the Cape Colony, which continued to expand eastward, and the actions of the Portuguese, who continued to trade in slaves from nearby Mozambique, were undoubtedly additional factors.

The history of power within the Zulu Kingdom has never been peaceful, and Shaka was constantly plagued by the machinations of his half-brothers eager to take his place. In 1828, he was finally overthrown and assassinated by one of them, Dingane. His death put a stop to Zulu expansionism, as his successor was more concerned with the need to secure his position than with further conquests. This did not prevent Dingane from being killed in turn by another half-brother of Shaka, Mpande, in 1840. The latter reigned until his disappearance in 1872 – something unusual, a natural death – but not before to have seen his two eldest sons engage in a fratricidal war for the title of heir to the throne. The eldest, Cetshwayo, defeated and killed his brother, succeeding his father when he died. At the same time, for half a century after Shaka's assassination, the Zulu kingdom continued to be engaged in raids and border actions against its neighbours.

One of the most lasting effects of Shaka's policy was the genesis of a Zulu culture martial and extremely aggressive . The impact was felt not only on the way of thinking about war at the strategic level, but also for the individual Zulu combatant. Shaka having extolled the pursuit of close combat, the Zulu warriors were particularly difficult to curb once the battle began. To return from combat without having "washed one's spear" in the enemy's blood was considered a disgrace. This perhaps explains why the Zulu have always stuck to the "buffalo horns" tactic invented by Shaka:in the absence of a real chain of command to transmit orders between the izinDuna and their men, the amabutho probably had no choice but to follow a standard battle plan, but known to all and therefore applicable even with minimal control over the troops. The Zulu's aggressiveness, their obsession with 'washing spears', added to the Zulu belief that slain enemies are disemboweled so their spirits do not return to haunt their killers, will give Europeans who encounter them an image of savagery. which will leave a lasting mark on the representation of the Zulus in Western culture. Added to this was an apparently incomprehensible relentlessness for a 19

th

European century:the Zulus, peaceful herders of cattle when they were not mobilized within their amabutho , took no prisoners – simply because the only way to win was, for them, to kill. This rule nevertheless obeyed an ethic, insofar as killing an unarmed non-combatant, for example, brought no glory to the Zulu warrior.

One of the most lasting effects of Shaka's policy was the genesis of a Zulu culture martial and extremely aggressive . The impact was felt not only on the way of thinking about war at the strategic level, but also for the individual Zulu combatant. Shaka having extolled the pursuit of close combat, the Zulu warriors were particularly difficult to curb once the battle began. To return from combat without having "washed one's spear" in the enemy's blood was considered a disgrace. This perhaps explains why the Zulu have always stuck to the "buffalo horns" tactic invented by Shaka:in the absence of a real chain of command to transmit orders between the izinDuna and their men, the amabutho probably had no choice but to follow a standard battle plan, but known to all and therefore applicable even with minimal control over the troops. The Zulu's aggressiveness, their obsession with 'washing spears', added to the Zulu belief that slain enemies are disemboweled so their spirits do not return to haunt their killers, will give Europeans who encounter them an image of savagery. which will leave a lasting mark on the representation of the Zulus in Western culture. Added to this was an apparently incomprehensible relentlessness for a 19

th

European century:the Zulus, peaceful herders of cattle when they were not mobilized within their amabutho , took no prisoners – simply because the only way to win was, for them, to kill. This rule nevertheless obeyed an ethic, insofar as killing an unarmed non-combatant, for example, brought no glory to the Zulu warrior.

Zulu's obsession with close combat also explains their contempt for firearms , often considered by them as unworthy of a true warrior. The Zulus were very early in contact with firearms and obtained them, but they never used them in large numbers, nor did they seek to modernize their armament. This state of affairs did not change, even after the Zulus had encountered troops armed with rifles in combat. As late as 1879, most of the firearms they had were antique flintlock muskets that had no doubt been made in Europe before Shaka reigned. Powder and bullets were in short supply and, partly for this reason, gun owners hardly ever had the opportunity to practice their uses, which generally made them poor shooters – but that didn't mean their bullets didn't. never found their target.

From 1820, the British tried to "anglicize in an accelerated manner the colony of the Cape, in particular on its eastern border. This leads them to confront the Xhosas, with whom the Dutch have already gone to war three times, and the English twice since they took control of the colony. Three other wars were still fought between 1834 and 1853. But it was the Xhosas themselves who ended up delivering the final blow:motivated by a millenarian prophecy, most of them massacred their own cattle and destroyed their crops. The ensuing famine between 1856 and 1858 made the Xhosas dependent on help from white settlers. Weakened, the Xhosas retain only a small territory – the “Cafrerie” – east of the Kei River.

- Previous

- Next>>