The Battle of Bouvines , which took place on July 27, 1214 in the North, opposed the army of the King of France Philippe Auguste to a German-Flemish coalition around Emperor Otto IV. The unexpected rout of the allies will offer a resounding victory to the Capetian, who will extend the royal domain and consolidate his power against his European rivals. It is one of the first battles, like Hastings, where a sovereign "tempts God", that is to say takes the risk of being stained with blood, and losing his life in battle. . Bouvines also marks a stage in the history of France because, following this victory, would have developed a "national feeling".

The Battle of Bouvines , which took place on July 27, 1214 in the North, opposed the army of the King of France Philippe Auguste to a German-Flemish coalition around Emperor Otto IV. The unexpected rout of the allies will offer a resounding victory to the Capetian, who will extend the royal domain and consolidate his power against his European rivals. It is one of the first battles, like Hastings, where a sovereign "tempts God", that is to say takes the risk of being stained with blood, and losing his life in battle. . Bouvines also marks a stage in the history of France because, following this victory, would have developed a "national feeling".

The context of the Battle of Bouvines

Since his return from the crusade, Philippe Auguste has never ceased to fight the Plantagenets (Richard Coeur de Lion, then Jean sans Terre), obtaining success after success, until to the conquest of Normandy in 1204. After England, the King of France took an interest in the divisions that were tearing the Empire apart, taking sides according to his interests, as he had done since the beginning of his reign.

The situation seems to be ideal when, to the Germanic quarrels, are added the problems of King John of England without Land with Pope Innocent III, who banned England in 1206, and excommunicated the son of Henry II in 1209! Philippe Auguste then decides to take advantage of this by entrusting his son Louis with the organization of a landing with the English enemy. It is however a failure and, in 1213, Jean sans Terre manages to find the papal graces while creating a coalition against his French rival, thus obtaining the support of the count of Boulogne, of Ferrand of Portugal (became count of Flanders), and especially Otto IV, whose rival Frédéric Hohenstaufen is supported by the Capetian.

The situation seems to be ideal when, to the Germanic quarrels, are added the problems of King John of England without Land with Pope Innocent III, who banned England in 1206, and excommunicated the son of Henry II in 1209! Philippe Auguste then decides to take advantage of this by entrusting his son Louis with the organization of a landing with the English enemy. It is however a failure and, in 1213, Jean sans Terre manages to find the papal graces while creating a coalition against his French rival, thus obtaining the support of the count of Boulogne, of Ferrand of Portugal (became count of Flanders), and especially Otto IV, whose rival Frédéric Hohenstaufen is supported by the Capetian.

Philippe Augustus decided to go on the offensive in Flanders in 1213. His son Louis (future Louis VIII) took his revenge against the English when they decided to open a new front by landing at La Rochelle:this is the French victory at La Roche-aux-Moines (July 2, 1214). In the North, however, the situation is more tense for the King of France because the allies meet, and Otto IV enters Flanders.

The opposing forces

Confrontation is decisive in more ways than one. One of the highlights is the presence of two great sovereigns, something still rare at the time. Because the battle is the risk of losing its legitimacy, which is acquired by victory, obviously decided by God.

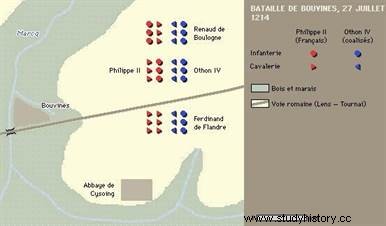

Philippe Auguste does not commit himself lightly. He is surrounded by several of his great knights and vassals, including the Duke Eudes of Burgundy, Guillaume des Barres, Gautier de Nemours, or the Count of Sancerre. The king is also assisted by the Hospitalier brother Guérin. The royal army is composed of about seven thousand combatants, including one thousand three hundred knights and as many sergeants on horseback; the infantry is made up of communal militias whose reputation is not always flattering. The whole is organized in three bodies, symbol of the Trinity, around the oriflamme of Saint Denis. The battlefield was perfectly delimited, and the bridge of Bouvines locked to allow a possible retreat of the French army through the swamps.

Facing the royal host, the allies line up one thousand five hundred knights, also the same number of sergeants at horse, but a little more infantry with Flemish militias and English mercenaries. In addition to Otto IV, the Count of Flanders Ferrand, the Duke of Brabant, the Count of Salisbury, Hugues de Boves and Renaud de Dammartin, Count of Boulogne are present.

Facing the royal host, the allies line up one thousand five hundred knights, also the same number of sergeants at horse, but a little more infantry with Flemish militias and English mercenaries. In addition to Otto IV, the Count of Flanders Ferrand, the Duke of Brabant, the Count of Salisbury, Hugues de Boves and Renaud de Dammartin, Count of Boulogne are present.

The Battle of Bouvines (July 27, 1214)

It was the French right wing, led by Brother Guérin, which began the fight. Composed of Burgundians and Champenois, it confronts the Flemish knights and their count, managing after several charges to break through their lines:Ferrand is captured! The center is more undecided:the most important troops oppose it, around the two sovereigns, Philippe Auguste and Otton IV of Brunswick. The infantry does not hold up against the cavalry charges, and it is soon a confused melee. The King of France is disconcerted, but barely saved by knights who intervene:the Emperor must flee.

On the left, the enemies know each other well since Robert de Dreux and Renaud de Dammartin are facing each other. The latter resists the longest, and must surrender only thanks to the reinforcement of Brother Guérin. The royal army then launched the pursuit, but most of the coalition leaders fled, including the Duke of Brabant and Otto IV himself. Philip II finally orders the end of the fighting on an uncontested victory, which will earn him the nickname of Augustus.

Consequences and posterity of Bouvines

The consequences are first visible at the level of the European balance of power:John Lackland, absent, is permanently isolated, and the English monarchy crisis worsens; Otto IV is decisively weakened in his fight against the Hohenstaufen, future Frederick II; the great feudal lords (in Flanders for example) had to give in to the Capetian monarchy. The latter asserts itself as the great power of the moment, and confirms its territorial conquests of previous years.

However, the consequences are even greater internally for the kingdom of France. Philippe Auguste quickly understands the advantage he can derive from this victory:great festivities are organized, during which the prisoners are exhibited. A real propaganda appears, like the Philippide of Guillaume le Breton, ten thousand verses composed between 1214 and 1224, to the glory of Philippe Auguste and the Capetian dynasty. The latter then tries to create around this victory (and himself) the premises of a "national feeling", an anachronistic term, but which shows the decisive nature of the battle.

However, the consequences are even greater internally for the kingdom of France. Philippe Auguste quickly understands the advantage he can derive from this victory:great festivities are organized, during which the prisoners are exhibited. A real propaganda appears, like the Philippide of Guillaume le Breton, ten thousand verses composed between 1214 and 1224, to the glory of Philippe Auguste and the Capetian dynasty. The latter then tries to create around this victory (and himself) the premises of a "national feeling", an anachronistic term, but which shows the decisive nature of the battle.

However, despite the efforts of the king and his propagandists, the impact of Bouvines during the lifetime of Philippe Auguste must be somewhat relativized. It would seem that it does not go beyond the Loire, whereas in the Empire it is almost unknown. There is therefore no real "national resonance" at this time.

The posterity of Bouvines comes later, especially in the 19th century, when historians, in their need to create a national novel, make it one of the dates of birth of the French nation. Thus, Ernest Lavisse writes:"Bouvines gave our country, with the security of its cradle, a beautiful figure in the world [...] this glory crowned the real France, the one whose history, without interruption, will continue to us . This is why the memory of Bouvines must remain national”.

Bibliography

- The Sunday of Bouvines:July 27, 1214 by Georges Duby. Nrf, 2005.

- The Battle of Bouvines, by Dominique Barthélémy. Perrin, 2018.

- Philippe II Auguste:The Conqueror by Georges Bordonove. Pygmalion, 2009.