Jules Ferry (1832-1893) is a French politician of the Third Republic, favorable to the republican ideas inherited from the French Revolution. Minister of Public Instruction during the Third French Republic, he passed several school laws between 1879 and 1882 which established compulsory, free and secular education for the first time in France. Jules Ferry is also the promoter of laws with fundamental consequences on political life and French institutions, since they establish republican freedom:freedom of assembly, freedom of the press and freedom of association. Its colonial policy, in particular the conquest of Tonkin, caused its fall. He will remain the archetype of the republican and progressive spirit of the end of the 19th century.

Jules Ferry (1832-1893) is a French politician of the Third Republic, favorable to the republican ideas inherited from the French Revolution. Minister of Public Instruction during the Third French Republic, he passed several school laws between 1879 and 1882 which established compulsory, free and secular education for the first time in France. Jules Ferry is also the promoter of laws with fundamental consequences on political life and French institutions, since they establish republican freedom:freedom of assembly, freedom of the press and freedom of association. Its colonial policy, in particular the conquest of Tonkin, caused its fall. He will remain the archetype of the republican and progressive spirit of the end of the 19th century.

Jules Ferry, a secular republican

Born in Saint-Dié in 1832, Jules Ferry began a career as a lawyer before being elected deputy and then mayor of Paris in 1870. In charge of supplying and maintaining order during the siege of Paris, he earned the unflattering nickname of Ferry-La-Famine. A fervent supporter of the young Third Republic, he joined the Freemasons in 1875, then became Minister of Public Instruction in the Waddington and Freycinet ministries. President of the Council from September 23, 1880, Jules Ferry played an essential role during these years when the Republicans were going to be able to apply the great principles they had inherited from the French Revolution.

Faithful to this spirit, Jules Ferry endeavored to give the state secular structures and fought against clericalism to deprive the Church of its power in society. Several laws secularized French customs, such as the one authorizing work on Sundays and Catholic holidays and the one removing the denominational character of cemeteries. The fight against clericalism, demanded by Gambetta in his 1877 speech, was in the spotlight and, sign of the times, it was the same year that the word "anticlerical" appeared in the Littré dictionary.

Jules Ferry's school reforms

It was in the field of education that Jules Ferry focused most of his efforts. He first reformed the Superior Council of Public Instruction, from which he excluded all personalities foreign to teaching, which amounted to excluding representatives of the clergy. Then he attacked higher education by filing in March 1879 a project tending to abolish the law of 1875 which had established the freedom of higher education and had granted to mixed juries, including members of private education , the right to confer university degrees.

It was in the field of education that Jules Ferry focused most of his efforts. He first reformed the Superior Council of Public Instruction, from which he excluded all personalities foreign to teaching, which amounted to excluding representatives of the clergy. Then he attacked higher education by filing in March 1879 a project tending to abolish the law of 1875 which had established the freedom of higher education and had granted to mixed juries, including members of private education , the right to confer university degrees.

Jules Ferry's project would hardly have aroused passions if it had not contained an article 7 which targeted religious congregations:"No one is allowed to direct a public or private educational establishment, of any order whatsoever, nor to give instruction there, if it belongs to an unauthorized congregation. This article concerned about 500 congregations, but, as Jules Ferry was not afraid to affirm loudly, one of them was particularly targeted, that of the Jesuits, "prohibited by our whole history".

Article 7 aroused considerable emotion in France. While the Republicans and the Ligue de l'enseignement, founded in 1866 by Jean Macé, rejoiced at the blow dealt to the congregations, the Catholics gathered in a Religious Defense Committee which organized a lion manifesto on demonstration against Jules Ferry, described as " new Nero". However, in July 1879, the law was passed by the Chamber of Deputies, but needed to be ratified by the Senate. The latter included many opponents of the law, joined by the old Jules Simon who considered article 7 "useless, dangerous, impolitic". On March 9, 1880, the senators, by 148 votes against 127, reject article 7.

On a Senate ballot, the government responded by taking two secrets, the first of which directed the Jesuits to disperse within three months and the second called on unauthorized congregations to put in order within the same period. The application of these decrees was not without difficulty. Many were the soldiers and the magistrates who preferred to resign from their functions rather than to direct the operations of expulsion of the congregations, some of which could only be done at the cost of the siege of the monasteries. More than 250 convents were closed and about 5,000 religious expelled.

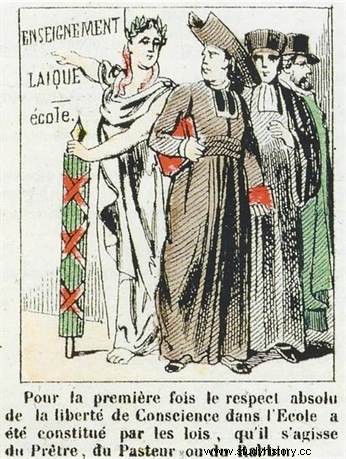

Secular school, free and compulsory

Snatch the little French people from Ignorance and the grip of the Church, such was the will of Jules Ferry and the team of men who, with him , tackled the reorganization of education, Ferdinand Buisson, Jean Macé, Camille Sée and Paul Bert. For the Republicans, in fact, any social progress had to go through the generalization of education to all children. The school became the ferment of patriotism and made it possible to fight against the “obscurantism” of the Church. Secular, free and compulsory education was the principle that dictated the laws granting all children the right to education.

Voted on December 21, 1880, at the instigation of the deputy Camille Sée, a law Established high schools for young girls . Under the Second Empire, Victor Duruy had tried without much success to create secondary courses for girls. "To give Republican companions to Republican men", Jules Ferry opened secular secondary education to girls. It was a great revolution in morals, so deeply rooted, even among free thinkers, was the habit of entrusting girls to religious schools. To train the teachers of these new female high schools, a female aggregation was created as well as the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Sèvres.

Voted on December 21, 1880, at the instigation of the deputy Camille Sée, a law Established high schools for young girls . Under the Second Empire, Victor Duruy had tried without much success to create secondary courses for girls. "To give Republican companions to Republican men", Jules Ferry opened secular secondary education to girls. It was a great revolution in morals, so deeply rooted, even among free thinkers, was the habit of entrusting girls to religious schools. To train the teachers of these new female high schools, a female aggregation was created as well as the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Sèvres.

The "cornerstone" of Jules Ferry's projects was to transform primary education, and he was supported in this by the Ligue de l'enseignement de Jean Macé, which campaigned with vigor for gratuity. A commission under the chairmanship of Paul Bert, assisted by three men from liberal Protestantism, Ferdinand Buisson, Théodore Steeg and Félix Pécaut, tackled the task of building the new primary school. They would have liked to impose the principles of gratuity, obligation and secularism all at once, but Jules Ferry preferred to have these reforms adopted gradually.

On June 16, 1881, the first law deciding on free primary education was passed. Then Ferry tabled a second bill providing for the obligation for all children aged six to thirteen to benefit from a school education. Total secularization was not yet decided, but religious instruction was replaced by civic instruction. This second law met with strong resistance from the right and was not passed until March 28, 1882. These laws consolidated the literacy and education movement in France. Jules Ferry's successors continued his work:in 1886 the law was passed secularizing primary school teaching staff.

The Second Ferry Ministry

Jules Ferry's second ministry would last for more than two years (1883-1885). This exceptional duration for the time allowed him to complete decisively the organization of the republic begun under his previous cabinet. According to “opportunistic” principles, Jules Ferry applies the Republican program point by point. The first important law he passed reformed the judiciary.

The incidents that had arisen at the time of the expulsion of the congregations in 1880 had shown the Republicans that it was necessary to get rid of a number of conservative magistrates . While the Radicals demanded the election of judges and an end to the tenure of the judiciary, Jules Ferry contented himself with passing the law of August 30, 1883, which suspended tenure for three months. This allowed him to carry out purges which seemed necessary to him.

In March 1884, the most important law of the second Jules Ferry ministry was discussed, the one granting the last of the political freedoms, the right of association. This was the work of the Minister of the Interior, Waldeck-Rousseau, who, in the face of resistance from the Senate, drafted a law authorizing only professional associations. It was, in effect, to recognize the formation of trade unions and their federation into unions. The Waldeck-Rousseau law, passed on March 21, 1884, made possible the progress of labor unionism. However, it was not welcomed without reservation by working-class circles and Guesde in particular reproached the government for not having also recognized the right to strike.

Colonial policy and the fall of Jules Ferry

Since the Republicans came to power in 1875, a new interest in colonization has emerged in France. In this regard, Jules Ferry had a decisive role thanks to the undertakings carried out in Tunisia, Africa and Tonkin, which, in his view, were to reinforce national greatness. Because it was essentially to erase the humiliation of Sedan and give France a prominent place in the world that the partisans of colonization engaged in their policy of expansion. And it took several years before a colonial doctrine was elaborated by Jules Ferry:in the great speech he delivered in July 1885, after the fall of his ministry, he justified imperialism on economic, military and patriotic grounds. French.

Since the Republicans came to power in 1875, a new interest in colonization has emerged in France. In this regard, Jules Ferry had a decisive role thanks to the undertakings carried out in Tunisia, Africa and Tonkin, which, in his view, were to reinforce national greatness. Because it was essentially to erase the humiliation of Sedan and give France a prominent place in the world that the partisans of colonization engaged in their policy of expansion. And it took several years before a colonial doctrine was elaborated by Jules Ferry:in the great speech he delivered in July 1885, after the fall of his ministry, he justified imperialism on economic, military and patriotic grounds. French.

But since the reawakening of the colonial idea, Ferry has come up against violent opposition from both right and left. To the argument of prestige put forward by the colonialists, their adversaries replied with the accusation of treason:the security of France was endangered by the adventurous initiatives of Ferry, who was accused of diverting their gaze from the blue line of the Vosges” and to forget Alsace and Lorraine. This "anti-colonial" party, whose real leader was Clemenceau, raged against the expeditions to Tunisia and Tonkin, which brought about the fall of the two Ferry ministries.

After resigning as president of the council on March 30, 1885, Ferry tried to run in the presidential election of 1887. Defeated in the legislative elections of 1889, he returned in the senate, which he briefly chaired in 1893, the end of his political career.

To go further

- Jules Ferry, biography of Jean-Michel Gaillard. Fayard, 1989.

- Jules Ferry, this stranger, biography of Éric Fromant. Editions L'Harmattan, 2018.

- History of secularism in France, by Jean Baubérot. “What do I know? », 2017.