During and after the Black Death, not all infected people were placed in mass graves, a new study reveals. Many of the deceased were buried in ordinary cemeteries.

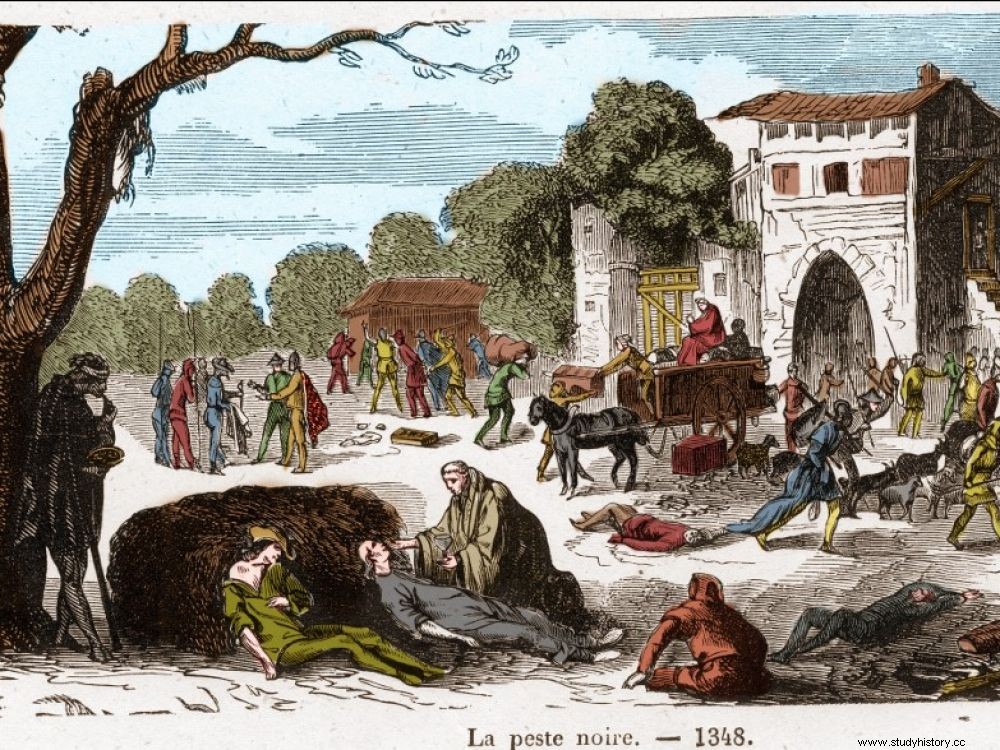

The Black Death in 1348. Engraving in "Histoire De France En Cent Tableaux de Paul Lehugeur".

As early as the mid-14th century in Europe, when the Black Death (1346-1353) would eventually kill between 40% and 60% of the population, some infected people were individually and carefully buried, reveals for the first time researchers from the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom). All the victims, whether during the episode of the Black Death or during the following epidemic episodes, were therefore not buried in mass graves.

No trace on the skeleton

The plague killed its victims so quickly that it left no visible traces on their skeletons, which has long complicated the task of archaeologists adept at osteological analyses. It is by considering contextual evidence such as time of burial and location - in mass graves - that they can easily identify plague victims. But historians and archaeologists already suspected that most of those killed had been buried individually in ordinary cemeteries, which had not been proven until now. Research therefore focused on the easiest sites to locate:mass graves.

By analyzing the teeth of people who died in the 14th century and after, researchers from the famous British university were able to identify the presence of Yersinia pestis , the bacterium responsible for the plague. Indeed, when affected individuals developed sepsis, Yersinia pestis could spread throughout the body, especially in the blood vessels present in the dental pulp.

As early as the mid-14th century in Europe, when the Black Death (1346-1353) would eventually kill between 40% and 60% of the population, some infected people were individually and carefully buried, reveals for the first time researchers from the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom). All the victims, whether during the episode of the Black Death or during the following epidemic episodes, were therefore not buried in mass graves.

No trace on the skeleton

The plague killed its victims so quickly that it left no visible traces on their skeletons, which has long complicated the task of archaeologists adept at osteological analyses. It is by considering contextual evidence such as time of burial and location - in mass graves - that they can easily identify plague victims. But historians and archaeologists already suspected that most of those killed had been buried individually in ordinary cemeteries, which had not been proven until now. Research therefore focused on the easiest sites to locate:mass graves.

By analyzing the teeth of people who died in the 14th century and after, researchers from the famous British university were able to identify the presence of Yersinia pestis , the bacterium responsible for the plague. Indeed, when affected individuals developed sepsis, Yersinia pestis could spread throughout the body, especially in the blood vessels present in the dental pulp. "Given the high level of mortality once a plague victim develops sepsis (...) find Y. pesti in a human tooth root almost certainly indicates that the person died of the plague ", explain the authors of the study published on June 17, 2021 in the journal European Journal of Archaeology .

Three plague pandemics

The first plague pandemic took place between the 6th century and the 8th century. The second pandemic began in Europe in the middle of the 14th century with a well-known episode:the Black Death which killed up to 60% of the population. Epidemic outbreaks then followed until the beginning of the 19th century. "The third pandemic began with the awakening of the old hearth of Yunnan in southern China, from where it reached Hong Kong in 1894 ", according to the Universalis website.

The mass graves were exceptional

The burials studied,"dating to between 1349 and 1561 AD, contained individuals who died of the plague during the second plague pandemic in Europe in the Middle Ages. Most had been buried in graves ordinary individuals and not in mass graves ", emphasizes the study. This is the first evidence that infected people were buried individually and with great care. Despite very dark times, special attention was therefore given to the majority of the deceased. " These individual burials show that even during plague outbreaks, people were buried with great care and attention, remarks in a press release Craig Cessford, co-author of the study. This is particularly noticeable at the convent where at least three of these people were buried in the chapter house (significant site of monastic life, editor's note)". This is a "major advance in archeology by emphasizing common burial practices in the Middle Ages rather than a few exceptional discoveries of mass graves ", say the authors of this research. Thus, between one and four million people died in England during the Black Death alone "but probably no more than a few tens of thousands were buried in mass graves ".

These discoveries do not prevent the presence of mass graves in the study area. Thus, infected parishioners were placed in a wide trench. But this new study "significantly improves our understanding of the plague and shows that even in the incredibly traumatic times of past pandemics, people tried to bury the dead as carefully as possible “, concludes Mr. Cessford.