The Val Camonica valley, located in the province of Brescia in the Italian Alps, is famous for hosting the world's largest collection of cave art, with more than 200,000 petroglyphs carved into sandstone rock and spread over different areas.

But what is even more amazing is that the oldest date from prehistory, from the Upper Paleolithic, and the most modern from the 19th century, covering a period of more than 10,000 years of history. For this reason they were recognized as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1979.

The vast majority of the oldest petroglyphs were made during the 8,000 years before the first millennium BC. Most of the most modern ones were made since the Iron Age by the Camunni, the people who still inhabited the area in Roman times. All of them are distributed among the eight different archaeological parks created in the municipalities of the valley.

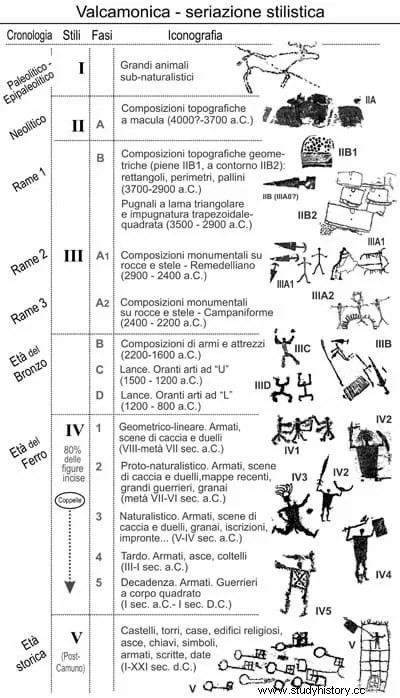

Thus, the first representations date back to the Mesolithic (8th-6th millennium BC) and would have been the work of nomadic hunter-gatherers, who left carved images of deer and elk on the rocks, some wounded with spears.

In the Neolithic, between 5500 and 3300 BC, the development of agricultural practices and the first permanent settlements brought new artistic motifs such as the figures of dogs, goats, bulls and geometric elements, rectangles, circles and points that could be topographical representations of the new cultivated land.

During the Chalcolithic or Copper Age, new symbols appeared such as human figures, plows and other tools, weapons and different animals, as well as astral elements.

Motifs that were stylized during the Bronze Age and the Iron Age in the 2nd and 1st millennium BC. And to which were added others representing cabins, labyrinths, footprints and hunting scenes.

In total, the petroglyphs belonging to the Iron Age are 70-80 percent of the total, being therefore the most prolific period. Among them stands out the so-called Map of Bedolina .

The Map of Bedolina

It is one of the oldest known topographic maps, engraved on a flat sandstone rock 9 meters long by 4 wide, in which crops, mountain paths and villages around the town of Bedolina are represented. , in the municipality of Capo di Ponte.

It consists of 109 topographic elements or patterns dating from between 1000 and 200 BC, representing roads, warriors, animals, wooden huts, and even a Rosa Camuna .

The Camuna Rose

It is one of the most curious symbols found among the petroglyphs of Val Camonica, which is why it has been adopted as an emblem by the Lombardy region.

It is a closed line that winds around nine cup marks, typical of prehistoric art, and that is represented both symmetrically (the most frequent) and asymmetrically or in the form of a swastika.

It is believed to be a solar symbol related to astral movement that evolved into a type of lucky charm, with carvings dating between the 7th and 1st centuries BC.

The name Rosa Camuna It is a modern invention based on its resemblance to a flower, but in reality we do not know what its original name was, although it bears a strong resemblance to other symbols from the same era throughout Europe.

From Roman times to the present

The Camunni were conquered by Rome, but that did not make the creation of petroglyphs disappear, which continued, although to a lesser extent, throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages, even reaching times as recent as the 19th century.

If during the Roman domination the creation of new petroglyphs slowed down, the beginning of the Middle Ages saw how it multiplied again.

This time with the carving of Christian symbols, such as crosses and keys, superimposing them on the ancient petroglyphs, in an attempt to Christianize places considered pagan.

Discovery at the beginning of the 20th century and the interest of the Nazis

The first to realize the importance of the engravings was the Italian-Swiss geographer Walther Laeng in 1909, although it would not be until the 1920s that the stones would begin to be studied and cataloged by researchers.

Then, in the years before World War II, the site aroused the interest of Heinrich Himmler and his Ahnenerbe, the Society for the Research and Teaching of German Ancestral Heritage, a pseudoscientific organization trying to gather proof and evidence about the history of the Aryan race.

Between 1935 and 1937 the organization financed the professor at the University of Halle, Franz Altheim, who, with his assistant Erika Trautmann, studied, inventoried and published many hitherto unknown prints from Camun. His theory was that the petroglyphs were the work of a supposed ancestral Aryan race.

After the war, it would be Walther Laeng who, this time with the help of a group of collaborators, would resume the investigations, compiling in 1954 the first map of engravings with the 93 rocks that would be included in the Parco Nazionale del Incisioni Rupestri (National Park of the Rock Engravings).

Starting in the 1960s, systematic investigations would bring new discoveries to light, and conservation work would begin.

According to UNESCO, the rock carvings of Val Camonica constitute an extraordinary figurative documentation of prehistoric customs and mentality .

And its systematic interpretation, its typological classification and its chronological study represent a considerable contribution to the fields of prehistory, sociology and ethnology . According to expert estimates, only 80 percent of existing petroglyphs have been discovered so far.