In November 1897 Alphonse Roux, a farmer, found in a field that he was working in the place called Verpoix in the municipality of Coligny (in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region), what looked like a cloth bag whose fibers had dissolved over time, buried about 30 centimeters underground. Inside there were 550 bronze fragments.

The pieces, acquired by the Musées de Lyon, were examined by the curator Paul Dissard, who came to the conclusion that they belonged to two different objects:a Gallo-Roman statue of just over a meter and a half in height, dated between the end of the 1st century BC and early 1st century AD. (about 400 pieces), and an incomplete calendar with almost half missing (149 pieces, of which 126 have inscriptions).

Both objects must have been destroyed around the year 275, as a result of one of the frequent Alamanni raids commanded by Chroco, the tribal chief who was said, exaggeratedly, to have destroyed all the Gallic temples.

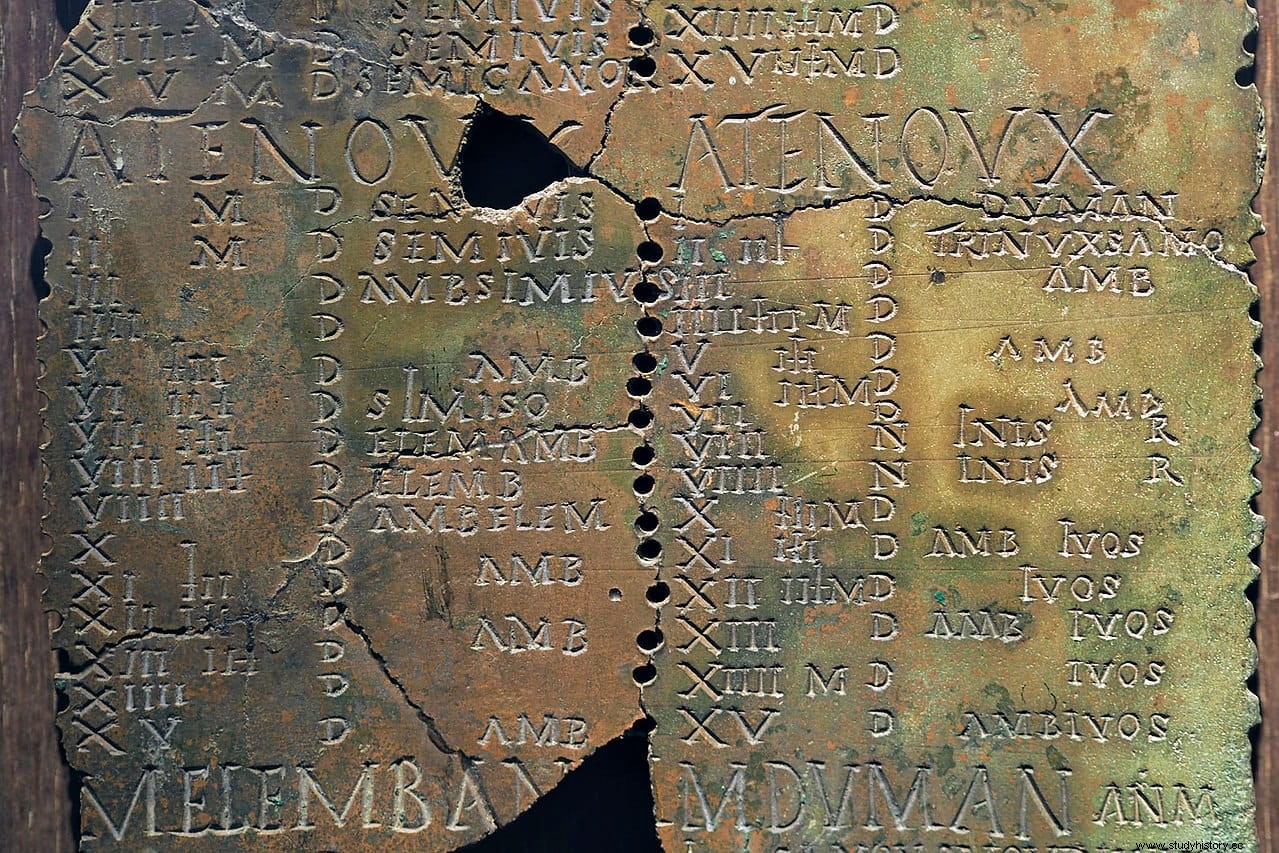

Dissard reconstructed the calendar in 15 days, giving it the form of a table of 1.48 by 0.90 meters, although the 149 fragments recovered barely cover two thirds of the total surface. It is organized in 16 columns of 8 blocks that represent 62 months in total. As in other calendars found in Rome, each day has a hole next to it, where a pin was placed to indicate the date.

The letters and numbers are in Latin characters, but the calendar language is Gaulish. It contains about 2,000 words, with about 130 lines per column, and is therefore the longest document in the Gallic language known. Up to 70 words that appear in it were not known before its discovery.

For this reason, it is a crucial epigraphic source for the study and knowledge of Celtic antiquity, and provides information on the conception of time, astronomical knowledge and the druidic tradition of the Celts.

In this sense, the druidic character of the calendar is evident, according to some experts, while others consider that it is a calendar for public use, similar to the Greek and Roman ones.

The important thing is that thanks to the Coligny calendar, and another found in Villards d'Heriad (of which only 8 small fragments remain), the Celtic calendar could be reconstructed.

It is a lunisolar calendar, that is, it takes into account both the phases of the moon and the sun. The months were lunar, and the year consisted of 354 or 355 days. This began with the month of Samonios (perhaps summer solstice or autumn equinox).

The months were divided into two halves, the fortnight being the basic unit of the Celtic calendar. In fact, Julius Caesar mentions that the days, months and years of the Gauls always began with a dark half followed by a light half.

Those months that had 30 days were called Matos (lucky), and the 29-day Anmatos (unlucky). The rest of the months of the year, after Samonios, would be:Dumannios, Riuros, Anagantios, Ogronios, Cutios, Giamonios, Simi Visonnios, Equos, Elembivios, Aedrinios, and Cantlos.

It is known from the Latin script, and the statue found alongside the calendar pieces, that the calendar belongs to a Gallo-Roman context from the end of the 1st century AD. And its complexity indicates good astronomical knowledge.

Both the calendar and the statue are on display at the Fourvière Gallo-Roman Museum. A reconstruction of the calendar can be seen at Coligny Town Hall.