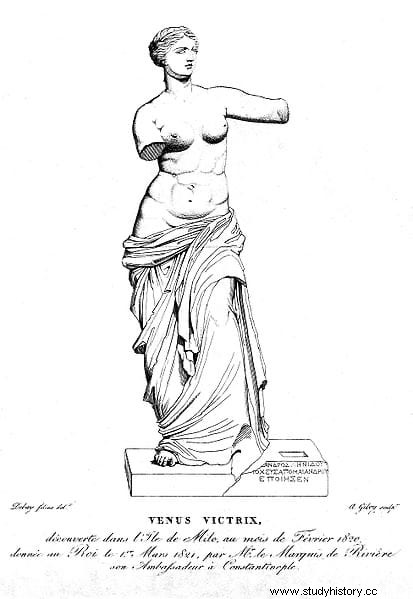

One of the most sensational discoveries in archeology and art occurred on April 8, 1820 on the island of Melos. Or at least that's the official version. Because the truth is that the discovery of the statue of Aphrodite, which would go down in history with the name of Venus de Milo , and his subsequent arrival in France, are shrouded in numerous mysteries and questions.

Already the same moment and the details of its discovery, as well as its authorship, are different according to the sources. Not even the date is absolutely exact. The possible time span is between February and April 1820, although historians generally accept April 8 as the most likely.

There is also no consensus on the name of its discoverer. He is attributed to a Greek peasant from the island of Melos named Giorgos (Yorgos) Kentrotas. Or Giorgos Botonis. In some versions he was accompanied by his son Antonio. In others, the discoverer would have been Theodoros Kentrotas (or Kendrotas) and the confusion with his son Giorgos would have made the attribution of the discovery fall on him.

How it was discovered and the French who happened to be there

The official version says that Kentrotas was extracting stone from some ruins on his land to build an enclosure when he found a cavity in one of the walls, in which several pieces of marble statues and inscriptions were hidden. Q>

About six years earlier the Roman theater had been discovered on the island, and the discovery of ancient artifacts, coins, pottery, jewelry and sculptures had attracted many Westerners in search of antiquities to Melos, then under Ottoman rule. /P>

Precisely at the same time that Kentrotas was unearthing the pieces of the statue, the archaeologist and lieutenant of the French army, Olivier Voutier, was there. Coincidence or not, Voutier, one of the many who had already scavenged the ruins of the theater, was exploring the island for ancient artifacts with two of his assistants and was just very close to Kentrotas. How close? Most likely, he was inspecting the same ruins where Kentrotas procured masonry.

The peasant, who must have been fully aware of the value of what he had found, tried to hide it from the French. According to one version, they realized that something was happening and went to see, while Kentrotas tried to throw dirt and stones to hide it.

The French insisted on taking an interest in what was there and helped the Kentrotas remove the earth and rubble again. The first thing they saw was the face of the statue, then unearthing the torso. By nightfall they had removed the two (or three) parts of a statue that, in total, weighed about 900 kilos (according to another version, one part was left in situ for not being able to unearth it). They immediately sheltered her in the Kentrotas stable, while Voutier dispatched his aides with messages for the French ambassadors and consuls in Constantinople and Smyrna, and the vice-consul in Melos.

In words written by Voutier himself:

How the French acquired the Venus de Milo

Louis Brest, the French vice-consul in Milo, tries in early May to negotiate the acquisition of the statue, making an initial offer of 400 piastres (the currency used in the Ottoman Empire) to the Kentrotas. But he had just sold it to an Armenian monk, who had acquired it for the dragoman (interpreter or translator) of the Ottoman arsenal Nicolas Mourosi.

On May 20, just as the statue was being loaded onto an Ottoman merchant ship bound for Constantinople, Naval Lieutenant Jules Dumont D'Urville together with Viscount Marcellus, secretary to the French ambassador, arrived at the embarkation point to prevent it and convince the local pasha to cancel the transaction and take the loot.

According to another version, D'Urville arranged the purchase with the Armenian (or Greek) monk, in order to elude the Turkish authorities. In any case, the result was that the Venus is loaded onto a French warship leaving Milo on May 23. She arrives in Constantinople on October 24 and on December 20 in Toulon. In mid-February 1821, the French ambassador, Charles François de Riffardeau, Marquis de Rivière, entered Paris triumphantly accompanying the statue.

And what happened to the arms, the apple and the plinth?

Along with the parts of the statue, two plaques with dedicatory inscriptions were found, as well as the plinth on which it could have been originally placed and on which the name of a sculptor appears:Alexander of Antioch. The inscription read:

This name has appeared in other ancient inscriptions, such as a statue of Alexander the Great found in Delos and which is also in the Louvre today.

The plinth and the inscription are known from drawings made during the time of the discovery, but both disappeared shortly after from the Louvre warehouses, so it has never been possible to verify whether they were part of the statue or not.

As for the arms of the Venus, there is consensus among historians that Kentrotas also later found fragments of the left forearm, as well as a left hand holding an apple or a pomegranate (this was too rudimentary to belong to the statue, according to Viscount Marcellus asserted). But the drawings made by Voutier show the statue as we know it today, without arms.

D'Urville also left a description of the statue, which certainly raises some questions and suggests that, like Voutier, he had seen it shortly after it was removed:

Kind Matterer, who was first officer of La Chevrette , the ship on which Voutier served, curiously does not confirm Voutier's story (ie, the account of his meeting with Kentrotas and the discovery). But, to confuse things more, he did leave a statement about the statue that adds more mystery to the matter:

And as if that were not enough, there is a sketch made in 1820, supposedly of the statue in the Kentrotas stables shortly after its discovery, which shows it with both arms, apple included, although we have not been able to confirm its authenticity.

One theory says that when D'Urville and Marcellus arrived on the Turkish merchant ship to seize the Venus, the Ottomans put up resistance, a small battle ensued and in the tug-of-war the statue hit the rocks destroying both limbs. Hardly anyone believes this story.

However, when Louis Adolphe Thiers was appointed President of France in 1870, he commissioned the ambassador to Greece, Jules Ferry, to travel to Melos to investigate the statue. Ferry managed to locate a son and a nephew of Kentrotas, both of whom claimed that the statue still had arms when it was found.

And in 1960 Turkey asked France for its return, under accusations of having stolen it. According to the Turkish government, the statue belonged to the Ottoman Empire (although by that year 1960 the island of Melos, where it was found, had been Greek for more than a century).

Surprisingly, Turkey claimed that if France returned it, they would restore its original arms, the location of which only three Turkish families knew. Of course France refused, considering such a statement as blackmail.

The Louvre has always argued that the original arms were never found, much less reached France. However, some of the fragments recovered by Kentrotas and whose belonging to the statue has always been controversial, such as parts of the forearms or the hand with the apple, are still forgotten in the museum's warehouses.

Since it arrived at the Louvre, the Venus de Milo has gone through many avatars, mainly during the two world wars.

What did not have to wait long was for it to become the most famous statue in the world, something that French propaganda commissioned, which made this 2.03-meter-high sculpture made sometime between the years 130 and 100 BC, in the paradigm of beauty.