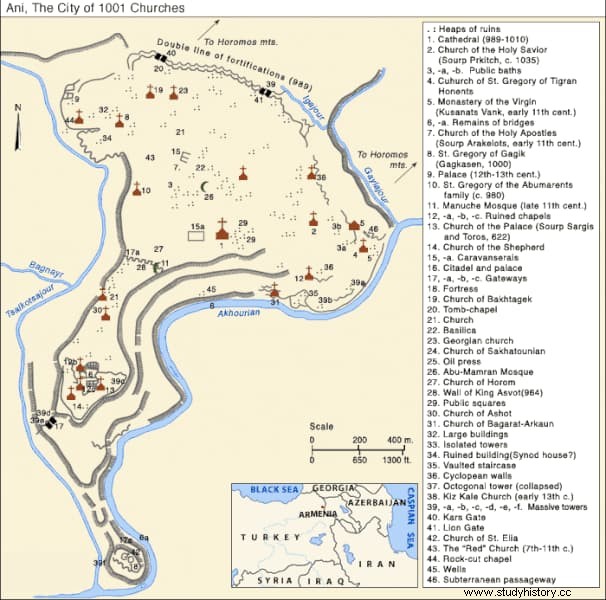

Ani It was an Armenian city of medieval origin that had between 100,000 and 200,000 inhabitants, a walled perimeter with up to 40 gates and so many religious buildings that it was known as the city of 1001 churches . Today it is a vast desert wasteland dotted with ruins and forgotten. The problem is that the political situation left it on the Turkish side of the border with Armenia.

The origins of Ani are not very clear, but it is known that the town grew from a strategic position on a hill, already described by Armenian chroniclers in the 5th century. Yeghishe and Ghazar Parpetsi mention it at that time as a possession of the Kamsarakan dynasty , a noble family of Parthian origin.

At the end of the 8th century, all the possessions of the Kamsarakans were incorporated by the Bagratuni family, whose founder Ashot Msaker was named Prince of Armenia by the Abbasid Caliphate in 804, starting a royal dynasty.

It would be one of his descendants, King Ashot III, who would move his capital to Ani in 961, making it the center of his kingdom and beginning its urban and architectural development. The Bagratid Armenian kingdom comprised most of present-day Armenia, but also eastern present-day Turkey.

During the following years Ani expanded and developed rapidly, and in 992 it also became the seat of the Catholic Patriarchs (the heads of the Armenian Apostolic Church). At that time the population already reached perhaps 100,000 inhabitants, and would continue to grow until its peak under the reign of Gagik I (989-1020).

Then the struggles for the succession would make the Byzantine Empire interested in the strategic location of Ani, in the middle of important trade routes with Persia and Arabia, and sent its armies to conquer the city, which finally surrendered in 1046.

His rule would not last long, because in 1064 the Seljuk Turks besieged the city for 25 days and, after capturing it, massacred the entire population and reduced it to ruins. According to the Arab historian Sibt ibn al-Jawzi, the dead were so many that they blocked the streets, no one could go anywhere without climbing over them. I was determined to enter the city and see the destruction with my own eyes. I tried to find a street where I wouldn't have to climb over the dead, but it was impossible .

But that was not the end of Ani yet. In 1072 the Seljuks sold the city to the Xadádidas, the Kurdish dynasty that would rule Armenia for at least a century after the fall of the Bagratuni. To assert their right, they married members of the former royal family and pursued a conciliatory policy towards the city's mainly Christian population.

When things started to go wrong, the citizens of Ani asked the neighboring Christian kingdom of Georgia for help. , who attacked and captured the city at least five times between 1124 and 1209. The last time it was conquered by the Georgian queen Tamar, who established her generals Zakare and Ivane as governors.

The first would definitively seize power, being succeeded by his son Shahanshah, who, considering himself the successor of the Bagratid dynasty, would establish a new one, the Zakáridas. Prosperity would return to Ani, new buildings would go up, and defenses would be reinforced.

This was not an impediment for the Mongols to conquer it in 1226, although allowing the Zakáridas to continue ruling it under vassalage. In the following centuries there were sieges, conquests by different peoples, and even an earthquake in 1319 and the capture by Tamerlane, the last of the great nomadic conquerors of Asia, in the 1380s. Finally in 1579 it became part of of the Ottoman Empire.

Little by little the city was declining and by the mid-seventeenth century there was hardly a small town left inside its walls. In 1735 its last inhabitants, the monks of the Kizkale monastery, abandoned the place, leaving it completely deserted.

The city was rediscovered in the first half of the 19th century by European travelers and dilettantes who noted its large and impressive public and religious buildings, as well as its double wall, which is still preserved. It was first excavated in 1892 by Russian archaeologist Nicholas Marr , and the works would extend until 1917, bringing to light numerous constructions and carrying out repair work on those at risk of collapse. A museum was created to house the tens of thousands of objects found in the excavations.

In 1918, during the First World War, the newly declared Republic of Armenia managed to evacuate at least 6,000 of the museum's objects, while the Turks advanced on Ani. Today these objects can be seen in the Museum of Armenian History in Yerevan. The rest was completely destroyed.

Post-war treaties gave Turkey control of the territory, and in May 1921, the Turkish government ordered Ani and all of its monuments to be removed from the face of the Earth . In his memoirs, the Turkish commander in charge of carrying out the order, Kazim Karabekir, states that he vigorously opposed carrying it out and that he never did. However, the current aspect of the city does not seem that this is completely true.

Today Ani is in the militarized border area between Turkey and Armenia, one of the reasons for her abandonment for so long. However, Turkey proposed in 2015 the inscription of Ani as a World Heritage Site, to which UNESCO agreed on July 15, 2016.

Among the monuments that remain standing is the cathedral , whose construction began in 989 and ended in 1001 following the design of Trdat, the most famous Armenian architect of the Middle Ages. His style has many similarities with European Gothic, which would precede several centuries.

Many churches remain partially standing, sometimes only small sections or fragments of apses, which gives the place a truly ghostly appearance.

Surprisingly, the minaret of the mosque has survived intact, unlike the building itself, which was the site chosen in 1906 for the creation of the museum. Likewise, fragments of canvases of the powerful double walls survive, and some of the towers built on it by different noble families during the 12th and 13th centuries.