Since ancient times it grew –in a vague place in the east Andalusian– an olive tree that ripened olives in a single day. Its oil had powerful, almost miraculous, healing qualities. Pilgrims flocked to pluck them on harvest day. They said that it was planted on the tomb of a Christian Holy Man, next to a spring. There are Islamic chronicles since the eleventh century that testify to this, but without specifying its exact location. For eight centuries there has been speculation about the place where it was planted. Even the Vatican claimed to take away the remains of the saint buried under the tree. But the only place that is reliably documented is on the slopes of La Sagra, between Huéscar and La Puebla de Don Fadrique.

Historical development

It was the 1st century AD, and we go back to the dawn of Christianity in Hispania. At that time the Apostolic Men – arrived in Cartagena. Cecilio, Eufrasio, Tesifonte, Indalecio, Exilio, Segundo and Torcuato– sent by Pablo, to catechize Baetica. They walked inland towards the Granada plateau and from Acci (Guadix ), a city that became the starting point for the bishops to distribute themselves throughout Baetica. Idols were worshiped in these lands... A short distance from the city they stayed to rest, while some who accompanied them came to buy food. The people, who were in full celebration of the festivals of Jupiter, Mercury and Juno, received them with great hostility and crossed them in a tumultuous way. In the flight, when crossing the bridge of the river, it sank, rushing into the waters the crowd of the pursuers.

Faced with this prodigious signal, the Men were very well received and the noble Luparía welcomed them into her home. , who after building a basilica for Christian worship and a baptistery, received the waters of baptism. Ending the course of her life with a happy death, they reached the possession of the heavenly homeland. In front of the sacred tomb of one of them, the miracle is performed through the intercession of the blessed confessors.

Each year on May 1, in front of the church where the tomb was, he had planted an olive tree that from the eve of that day flourished and in twenty-four hours was covered with fruitful fruit. The next day the whole town went to pick the olives that they kept carefully as a remedy for their illnesses.

This legend is already documented since the 7th century , and it could be "written" by a Mozarabic from Baetica, who moved to the north of Spain, after the Arab invasion.

The legend of the miracle of the olive tree appears for the first time in the Abdon martyrology , dated in the year 859 AD, referring to the Apostolic Men and in which it is said that the olive tree was next to the tomb of San Torcuato, while the martirologio Cerratense specifies that said olive tree was planted by the Apostolic Men in front of the church, without indicating which church it is. All the Mozarabic calendars place the celebration of the feast of the Apostolic Men on the first day of May. It shows the activity still at that time of a Christian community in Andalusia, with a monastery with monks, who preserved and still venerates the tomb of a martyr in their church, important enough for the kingOrdoño II (914-924), who reigned in the year 305 / 917-918, was interested in the recovery of his relics.

But far from being lost in the mists of time, with the Arab invasion, our legend again aroused the interest of travellers-geographers, in search of a land of wonders.

The abundance of documentary sources from the Islamic period ensures that in al-Andalus there was one of the only two miraculous olive trees (the other was in Alexandria ).

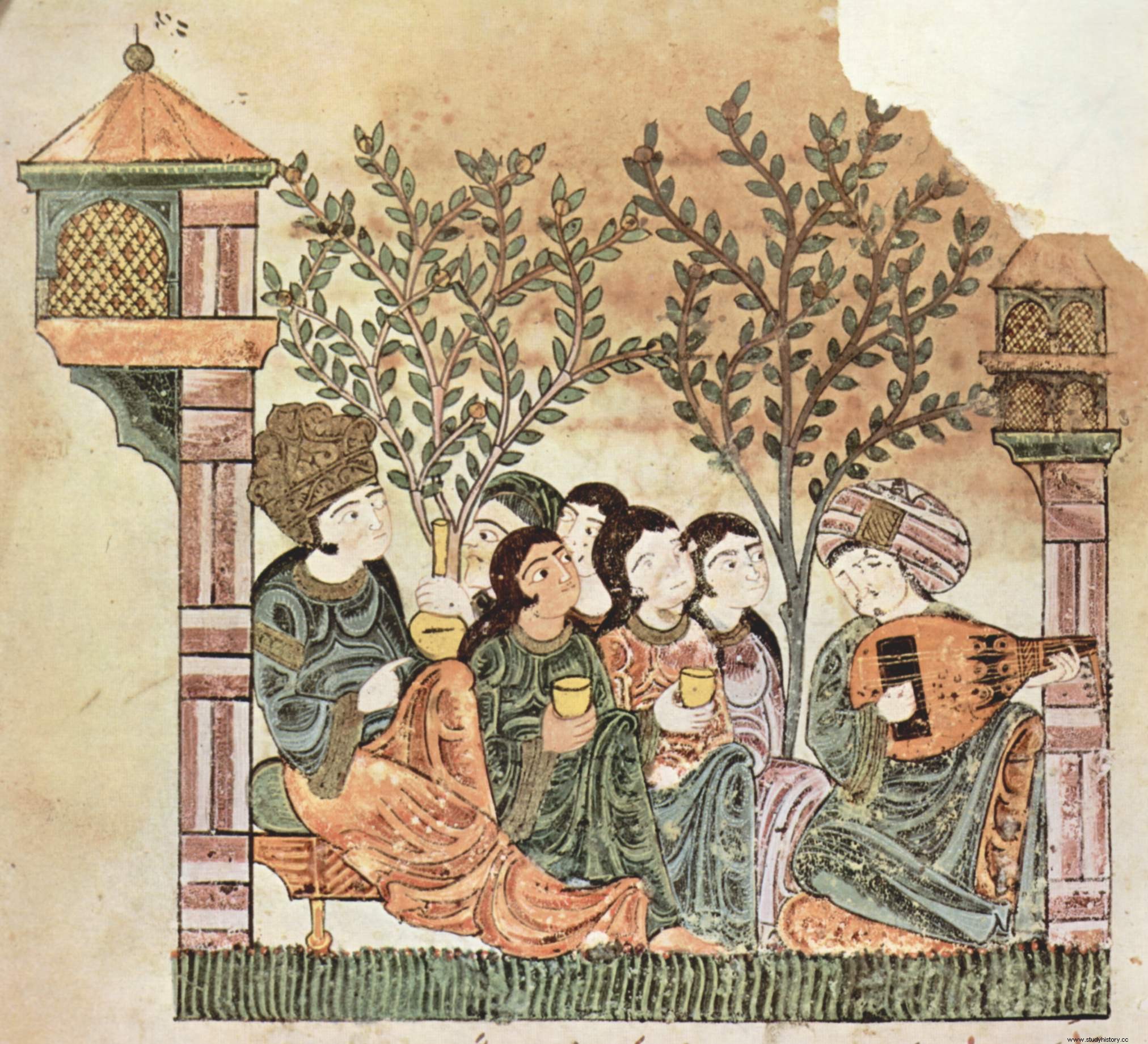

A true miracle. This is how the people of the XI and XII centuries understood it. , so that the place became a very important point of pilgrimage for those people, in search of miraculous solutions to human hardship. They attributed the miracle of the miraculous olives to the fact that a good man, a hermit, a martyr had been buried under it. from Roman times or perhaps from the caliphal persecutions. But nobody left the exact place written.

Arabic references

Al-Udri (1003-1085) was a geographer from Almería. He wrote a descriptive book on the Cora de Tudmir (kingdom of Murcia), which covered lands in Levante and the Granada area. In his chronicle it says that, next to a church, which was supposed to be Mozarabic, located in a mountainous area and located in lands of the Lorca demarcation, very close to a castle called Mirabayt, is the miraculous olive tree. Obviously, in the 11th century the mountainous area of La Sagra-Santiago de la Espada must have been under the jurisdiction of Lorca. Mirabayt castle was none other than Mirabetes.

Shortly afterwards (around 1130-50), the Granada geographer Mohammed Ibn Abi Bakr al-Zuhri He referred to the same matter of the miraculous olive tree. In this case, he tells it in the first person because he says he attended the pilgrimage and saw with his own eyes what happened there. He assures that there was a crowd gathered around the tree, waiting for the olives to ripen. Such was the desperation that the people began to pluck the fruits before they were fully black, fearing that they would be left without any.

Lastly, Himyari later narrates the same legend, but adds more information about the relics of a martyr that the convent preserves” Ibrahim ben Yahyá al-Turtusi recounted that the king of the RUM (Christians, Pope John XII) told him in the year 305

Christian references

In the 10th century Ibrāhīm ibn Yaʿqūb or Abraham ben Yacov was a Jew from Torsosa who engaged in trade across Muslim and Christian lands in Europe. He lived at the end of the 10th century. Around 960 he arrived in the Holy Germanic Empire and, by order of Caliph Abderramán III, served as ambassador to the court of Otto the Great.

he coincided in his embassies to Central Europe with Bishop Recemundo de Ilíberis, that is, the Bishop of Granada, who also carried out palatial work in Medina Azahara. Recemundo (in Arabic, Rabbi Ibn Zyad al-U(s)quf al-Qurtubi), is the author of the famous Mozarabic Calendar . We do not know through the mouth of which of these two, the merchant or the bishop, reached the ears of Pope John XII the news of the miracles that the olives planted on the corpse of a holy man of the Church worked. This papal embassy to Medina Azahara is documented in the year 961, although when the emissaries arrived at the capital of the Caliphate, the last Abderramán had already died. The holy man they were looking for was none other than San Torcuato and the place mentioned by the chronicles would be close to Baza. But by that date the remains of Saint Torcuato were no longer in al-Andalus, since in 777 they were exhumed and taken to Santa Comba (Orense) and later to Celanova, where most of his bones are found.

The Tradition of Santiago de Compostela

But our story does not end here. These texts will be handled late in the Codex Calixtinus to alter and innovate the protagonism of Santiago el Mayor, but compiling the lives and works of the Men, because they are essentially the same story.

La Sagra, the only documented place

Its existence at the beginning of the 16th century is fully documented. Whether or not he worked miracles is a matter of personal belief. In the Historical Archive of Huéscar there is an order from the mayor, Gonzalo de Peñalosa , by which he authorizes the neighbor Martín Galán to arrest and imprison those who cause disturbances with the devotees who went on pilgrimage to the holy olive. The writing is dated August 11, 1515. It is also clear that the tumult that was to form would be similar to the one described four centuries ago by Arab geographers.

The olive is next to the hermitage, which was built to venerate the Saints Alodía and Nunilón , brought from Aragonese lands. At the foot of La Sagra and close to the Mirabete castle , which the Arabic sources mention.

Bibliography

- JIMENEZ MATA, Mª Carmen. "About the 'ajā'ib of the wonderful olive tree and its Christian version in the Miracle of Saint Torquatus". Notebooks of History of Islam, 1 (1971), pp. 97-108 + 3pp.

- MONFERRER SALA, Juan Pedro. "Marginalia semitica I:Additions on five pending questions". Miscelaneous of arabic and hebrew studies. Arab-Islam section. Vol 56 (2007). ISSN 0544-408X, p. 255-268.

- CARMONA GONZALEZ, A. (1993). "Note on religiosity and beliefs in al-Andalus, regarding the study of the cave of La Camareta". Antiquity AND Christianity , (10), 467-478.

- FONTENLA BALLESTA, S.:«Myths in Andalusian Lorca», Alberca,6, Lorca, 2008, pp. 107-111